|

Part 3:

As we enter the final chapter of her life, Betsy Bigley is calling herself Cassie Hoover, a widowed mother of a young boy. We are still in "The Twilight Zone," but headed for "The Odd Couple," "Who Do You Trust?" and, finally, "Break the Bank."

As usual in this story, the next obvious question has no definitive answer, that question being, how did Cassie Hoover meet Dr. Leroy Shippen Chadwick? And I tend to distrust the usual answer to the obvious question that follows — How rich was Dr. Chadwick?

The con woman returned to Cleveland for the last time in 1895, and there's widespread agreement she operated a brothel, though she might not have been one of those madames you see in films and TV, the ones who greet her customers and summon her girls to prance around in front of them.

No, the usual story is Cassie Hoover, by any name except Lydia Devere, was still a clairvoyant, but with a new sideline — masseuse. As such, she lived in the building that housed the brothel, but operated out of a separate apartment.

Explanations for her meeting with Dr. Chadwick include (A) bumping into him on the street, (B) making an appointment with him about a medical problem, or (C) awkwardly having her first conversation with him outside the building when he was on his way to see a prostitute.

And though I don't buy it, Milena Evtimova, in an article for The Oberlin Review (November 10, 2006) offers my favorite explanation:

"When the famously-rich doctor entered the brothel Bigley introduced herself as a widow who had recently taken on the position of the manageress of 'this home for girls.' When Chadwick clarified that this was not a home for girls but a 'house of very ill repute,' Mrs. Hoover fainted and asked the dear doctor to take her away from that place."

When she moved into this building is uncertain. It's also possible that she owned the building. Several newspaper stories from 1904 claim she'd made a lot of money in Toledo before her arrest, and that she had her own house. If this is true, she must have had a nest egg waiting for her while she was at the Ohio Penitentiary. |

| * * * |

An Oberlin theory

Released from prison in 1893, she apparently bounced back and forth between Cleveland and Woodstock until 1895, and when she was in Cleveland previously, she stayed with her sister, Alice York, with whom she seems to have had a stormy relationship. Curiously, it is seldom mentioned that she had two other sisters who had moved to Cleveland, Emily Bigley Pine and one — her name may have been Jessie — who married a man named Campbell. Mrs. Campbell soon returned to Canada.

I came across one story in a generally reliable newspaper that placed Alice York not in Cleveland in 1893, but in Oberlin, raising the intriguing possibility Lydia Devere, before she became Cassie Hoover, had met banker Charles T. Beckwith a lot earlier than either one of them admitted in 1904. The story misidentifies Mrs. York as Mrs. S. M. Yerke. (Alice Bigley's husband was Standish Milton York.): |

Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, Tuesday, December 6, 1904

OBERLIN, Ohio, December 5 — C. T. Beckwith has lived in Oberlin more than fifty years. His reputation is that of a sort of rural Russel Sage. He was noted for his shrewdness in money matters. He was a money lender and made a big success at it. Handling money has been his lifetime vocation. No man had ever sold him a “gold brick.” He was penetrating,, suspicious and exhaustive in looking up credits. He was behind the gas company and the electric company.

When Albert Johnson, former president of the Citizens’ National Bank, was killed in a Colorado railroad accident, and Beckwith, then vice-president, succeeded to the presidency, everybody said he was the right man. That was five years ago.

Though President Beckwith asserts he became acquainted with Mrs. Chadwick only four years ago, it is believed that one Madame Devere knew all about Beckwith eleven years ago. Mrs. Chadwick’s sister, Mrs. S. M. Yerke, lived here at that time. Madame Devere visited Mrs. Yerke, and the stay extended beyond a year.

“She lived very quietly here,” said a neighbor. “Whether Madame Devere had any dealings with Mrs. Beckwith at that time, I cannot say. We heard, after she left here, that she was living in Cleveland. She did not pose here as a clairvoyant, but attracted a good deal of attention by her beauty and exclusiveness."

Now he believes Mme. Devere had just been released from the Columbus Penitentiary and was planning a conquest of banks. The Yerkes moved to Cleveland several years ago.

|

|

Anyway, Cassie Hoover could have been in Cleveland, telling fortunes, rubbing backs and supervising prostitutes, by late 1895, a year after Dr. Chadwick became a widower and the single father of a daughter born in 1885. He lived in a larger-than-necessary house his father, Elihu Chadwick, had built on Euclid Avenue. Elihu died in 1882, the same year his son, Leroy, was married. In addition to his daughter, Dr. Chadwick lived with his 82-year-old mother and his disabled sister, Clara, 51 years old in 1896.

I find it interesting that Dr. Chadwick is often described as suffering from an orthopedic condition (cause undertain) that gave him discomfort in one of his shoulders. Brian Benoit, in his story, "Nerves of Steal: Cassie Chadwick, 'Patron Saint of Confidence Women'," on Readex Blog, says the future Mrs. Chadwick was able to provide comfort with a massage.

Karen Abbott writes much he same thing, though she says Dr. Chadwick was suffering from rheumatism in his back. Others say his discomfort was from an old arm injury. Overall, Dr. Chadwick was in rather poor health, prompting him to curtail his practice and seek relief in trips abroad, something that increased after he married Cassie Hoover. To me, traveling seems a poor remedy for Dr. Chadwick's previous physical ailments, though it may have been the best way to avoid the headache his second marriage would soon become.

Whatever, I've concluded the two of them met not by chance, but when Dr. Chadwick went to Cassie Hoover for a massage. And if he asked, "What's a nice woman like you doing in a building with a brothel?", I'm certain she came up with a clever response, one that expressed dismay and ignorance, perhaps a promise to seek a better residence. For sure she gave him the impression she could well afford a better place, and most likely she could.

She must have been one hell of a masseuse, or perhaps it was the effect of her hypnotic eyes, because it wasn't long before she became Mrs. Chadwick. Sort of. |

| * * * |

Just how rich was Dr. Chadwick?

According to the Washington Evening Star (August 28, 1908), Dr. Chadwick's estate was worth about $50,000 when they were married. There's no mention of wife's wealth, though if stories out of Toledo from her days as Lydia Devere can be believed, she might have put away a nice chunk of change for a rainy day.

I realize we're talking about the 1890s, but even then $50,000 wouldn't be enough to qualify as particularly wealthy, not for someone who lived on Euclid Avenue, about a mile east of John D. Rockefeller.

Karen Abbott describes Dr. Chadwick as "a wealthy widower and descendant of one of Cleveland's oldest families," but I believe that's a tad misleading, though other sources say much the same, including the first mention of the doctor in a long Chicago Tribune story (December 4, 1904).

It's what that article says next that puts Dr. Chadwick in better perspective:

"Dr. Chadwick's father located in Cleveland 35 years ago [1869], coming from Pennsylvania, where he owned land on which big oil wells were struck, which made him a man of considerable wealth. Soon after he reached Cleveland, he built the mansion at 1824 Euclid Avenue, which has figured so prominently in the tremendous exploits of Mrs. Chadwick."

This means Dr. Chadwick was not a native Clevelander, and his family could not have been one of the city's oldest. Also, Dr. Chadwick's father, Elihu Chadwick Jr., was relatively wealthy before he sold his land in Venango County, Pennsylvania, near Oil City. Elihu Chadwick Sr., a Revolutionary War officer, had much to do with developing settlements in western New York and northwest Pennsylvania, and Elihu Jr. was land rich as a result. His home in Pennsylvania was part of the Underground Railroad during the Civil War, with a special hiding place constructed in the basement.

Elihu Chadwick Jr. and his wife, Isabel, had nine children. Leroy was number eight, being born in 1853. The first born, James Dodderidge Chadwick (1836), served in the Civil War, and remained in Venango County when his parents moved to Ohio, probably to get away from all the oil wells being constructed on and near the land he had sold. His son, James, settled down in the small city of Franklin, where he became a successful lawyer.

Only six of the nine children of Elihu and Isabel Chadwick were alive when the Chadwick family settled in Cleveland in the house Elihu built on Euclid Avenue, but when he died in 1882, much of his wealth was distributed to four of Dr. Chadwick's siblings, though he remained at the house and cared for his mother and his impaired sister, Mary Emma.

It was assumed by people in Cleveland that Dr. Chadwick was rich, but that Chicago Tribune story says he was known for his work among the poorer people of Cleveland, and often treated them free of charge. It also was written that he made a specialty of the study of insanity and was considered an expert in this line. You'd think he would have noticed some disturbing signs in the second Mrs. Chadwick, who had once been judged not guilty in a criminal case by reason of insanity. It's doubtful she ever shared that information with him.

Because his own health was iffy, Dr. Chadwick practically abandoned his practice after he married Cassie, which is one reason I believe it was more than a good massage the prompted his proposal. I believe the woman's biographers have badly judged her attractiveness, and photos of her in 1897, the year she and Dr. Chadwick were married, show a good-looking woman who outwardly seemed a good catch for a 43-year-old widower who had some daunting obligations. He might well have thought he was getting a nice, well-to-do woman who'd lift much of the burden from his shoulders. I don't know why, but stories about the man had me thinking he was a bit of a hypochondriac who might have been tired of caring for his mother and sister while his siblings, who had scattered to the four winds, seemed to be doing so well.

For sure, the man was weary, too weary to rein in the second Mrs. Chadwick who took charge of the house as soon as she moved in, bringing her son, Emil, with her.

|

| * * * |

'I pronouce you Mr. and Mrs. Schadwick'

If Dr. Leroy Chadwick were weary, he also indicated wariness in the way he handled his first wedding ceremony with Cassie Hoover. That's right. This couple was married twice, the first time on February 5, 1897, in Pittsburgh, and it wasn't exactly legal, not if you count the lies that were told when the marriage license was issued to Dr. Chadwick, who applied by himself. At the time, it was permitted for prospective bride or groom to take out a license for both of them. Since then, the law was changed, requiring both members of the couple to be present when a marriage license is requested.

|

New York Sun, December 2, 1904

PITTSBURGH, December 1 — The most interesting exhibit in the office of the marriage license clerk of Allegheny County today was No. 9647, series C, a license issued February 5, 1897, to Dr. Leroy L. Schadwick of 1824 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, and Mrs. Cassie L. Hoover of 166 Franklin Street, Cleveland.

It is evident that at the time, Schadwick, as the Cleveland physician wanted himself known, did not care to have the fact of his marriage to Mrs. Hoover known.

Across the face of the outside of the license is written "Don't publish," which means that the one taking out the license asked that the facts in that particular case be kept away from the newspapers. Hundred handled this marriage license today, and almost every one called attention to the fact the name was spelled "Schadwick" instead of "Chadwick."

It was made additionally strange by the plain evidence that Chadwick was the name of the Cleveland doctor who took out the license as Schadwick, for the Rev. Dr. Jolly. Chadwick's cousin, who performed the ceremony in the Hotel Anderson that very day, and who knew the real name, evidently declined to have anything to do with the Schadwick proposition, as his return slip, enfolded with the "Schadwick" license, speaks of the name as "Chadwick."

Nor did "Mrs. Hoover" evidently care to tell a great deal about herself. The questions were answered by Dr. "Schadwick" for her. They tell that she was born in New York State on March 28, 1863, and at the time of application was 33 years of age.

|

|

The license also said she had been married before and that her marriage relations had been severed by death.

Whether Dr. Chadwick did this to give himself an easy out from the marriage, who knows? If so, Cassie Chadwick passed the test and they had a second wedding on August 26, 1897, at Windsor Methodist Church, in Windsor, Ontario, just inside Canada, along the Detroit River. This time Dr. Chadwick gave hs correct name, but "Mrs. Hoover" again lied about her name, age, birthplace and parentage, listing her father and mother as Osborne Riddleman and Katherine E. Turner, which may indicate she was stealing the identity of her one-time Cleveland landlady. Cassie actually was 39 years old when she married Dr. Chadwick, and I suppose it's possible she told him her date and place of birth, and he believed her — but how to explain her wish to get married in Canada if she claimed to have been born in New York?

Years later both weddings would be declared invalid, but she eventually, by Ohio rules, became Dr. Chadwick's common law wife. |

|

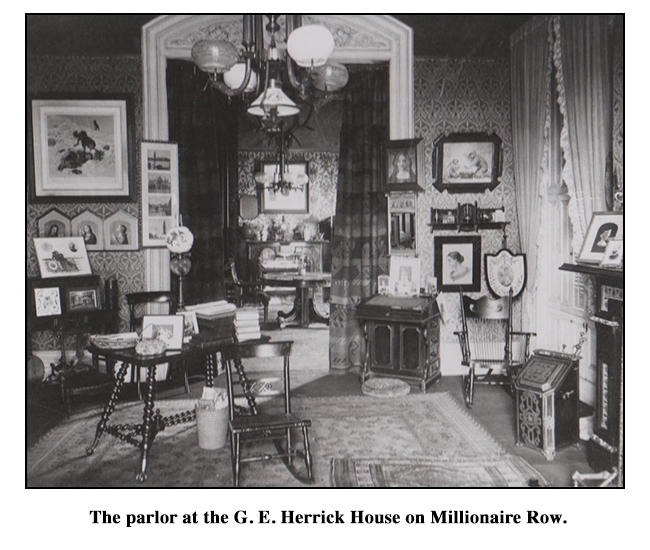

Though she hadn't yet staked her claim to a blood relationship with Andrew Carnegie, the new Mrs. Chadwick apparently was doing quite well with her various cons, or money she had saved from the past few years. And her new husband gave her the green light to spend whatever it took to decorate the house to her taste. That was a big mistake.

About the house. Despite what many have written, it was not part of Cleveland's Millionaire Row. The street numbering system, changed in 1923, gives a clearer picture of the location of the Chadwick house, which was demolished in 1910 and replaced by the Euclid Avenue Temple. The temple relocated in 1956, and the building was sold to Liberty Hill Baptist Church, which remains at that location today in the building that was the Euclide Avenue Temple.

When the Chadwicks lived in their house, its street number was 1824, and the nearest intersection was Genesee Avenue. Today its number is 8206, and Libert Hill Baptist Church sits at the intersection of Euclid Avenue and East 82nd Street. Millionaire Row went out of existence in the 1920s; when it did exist, the rich folks' mansions ran along Euclid from East 9th Street to East 55th, though some sources draw the easternmost line at East 41st Street. So the Chadwick house was about a mile away.

|

| Granted, the Chadwick house was bigger than the average American house, but it was plain-looking on the outside, and, until Cassie came along, drab on the inside. That would soon change, thanks to Mrs. Chadwick's first Christmas present for her husband. |

"Cassie Was a Lady," by George Condon

On Christmas Eve, Cassie took Leroy to a theater party. While they were thus engaged, an army of moving men and decorators rolled up to the sedate mansion and took it over in a fury of activity. By the time the Chadwicks returned, it was no place like home; not the home they had left only a few hours before, anyway, and not like any home that Euclid Avenue ever had seen before, likely.

Every stick of furniture was brand, spanking new. In place of the comfortable old dark pieces with their delicate antimacassar accessories and the frowning portraits of gaunt Chadwickian ancestors, all was gaiety. The prevailing color in the new scheme of things was gold. Lush new Persian rugs now covered the floor, and the dull plush furniture had been replaced by tables and chairs with hand-painted designs, elegantly tooled leather, and artistically carved Circassian walnut cabinets. Dr. Chadwick himself was a pretty hue somewhere between fuchsia and lime green as he groped for his dangling pince-nez and tottered about in aimless shock. |

|

| No specific Christmas is mentioned in the stories I've read about this gift, but I'm guessing it was their second Christmas together, in 1898, because that year Dr. Chadwick's life became less complicated, his house less crowded, with the death of his mother, Isabel Jolly Chadwick, on March 25, and the passing of his sister, Clara Catherine Chadwick, on October 13. His mother was 84, his sister 53. However, I suppose it's possible she began her renovation of the interior of the Chadwick house a year earlier. |

| * * * |

Money can't buy taste

In a story recalling Cassie Chadwick's adventures, the Minneapolis Journal (December 19, 1904) estimated the cost of that Christmas present exceeded $10,000, or about a quarter of a million dollars in today's market.

That was just the beginning of a spending spree that had many Clevelanders talking, but much of what they said was not complimentary. |

Auburn (NY) Demorat-Argus,, March 7, 1905

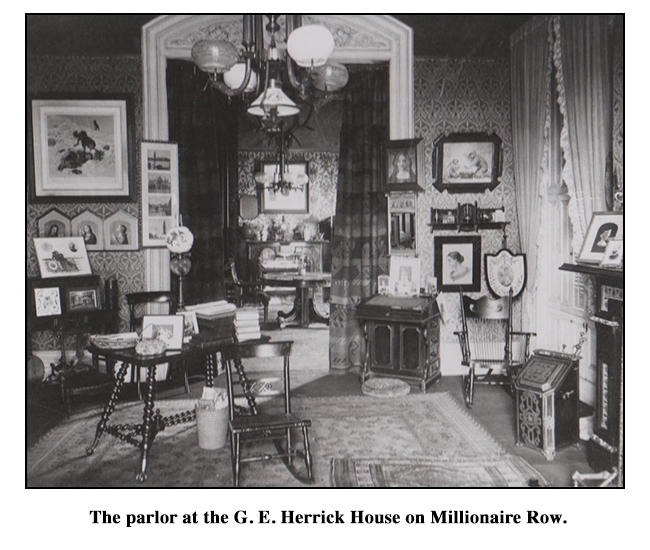

She furnished the Chadwick mansion according to her own idea of elegance. Her utter lack of taste is apparent at a superficial inspecion of the interior of the house, with its grotesque array of costly rubbish, as many would term it.

The rooms are crowded with cabinets. The cabinets, mantels and every available space display a heterogeneous collection of bric-a-brac, undoubedly expensive, but utterly abhorrent to sane ideas of home adornment. The little music room is dwarfed by an immense pipe organ. The walls are covered with picgures of varying merit, for which she paid exorbitant prices.

Among the bizarre furnishings is an enormous clock, which covers a table in the reception room. This machine, wich queer sprockets and chains, glittering with gold plate and onyx,is silent and motionless under its huge glass dome.

|

|

Enough already! Seems people who were around at the time enjoyed making fun of someone who didn't belong anywhere near the high class residents of Millionaire Row, and those who wrote about her a hundred years later made it a point to say she was homely, so how could she have wrapped so many men around her finger?

No doubt the woman belonged more in prison than in any home on the outside, but I found one interior photo of a Millionaire Row home that belonged to G. E. Herrick, who made his millions in railways — more along the lines of streetcars than long-haul railroads, I think. Anyway, I can't imagine Cassie Chadwick's interior decorating was any worse than whoever put this room together: |

|

But it is interesting that today those with a vested interest in the history of Cleveland's Millionaire Row make a point of mentioning Cassie Chadwick as one of its more famous residents when she actually wasn't — a resident of Millionaire Row, that is.

As for her appeal, she began her biggest con when she was 44 years old, and couldn't do it with her looks, except on a facial expression that convinced people she could be trusted. Then she set out to exploit two other male weakness — greed and their low opinion of a woman's intelligence. She spent her last three years engaged in crook on crook crime. Technically, she was the guilty party, but what the bankers charged her for her loans was little short of highway robbery. Not that she cared. |

| * * * |

A legend is born

It's difficult to know how much to believe of the many things written about Cassie Chadwick's spending sprees. The Chicago Sunday Tribune (December 4, 1904) had this to say:

"There is not a store in Cleveland of any prominence with which Mrs. Chadwick has not had dealings. At some of them she has spent thousands and thousands of dollars, and has paid spot cash. She tried no trickery with them when she wanted anything. No person with millions at his command ever bought with a more lavish hand than did Mrs. Chadwick, and when she bought, she had the money to pay for it.

"She juggled with no securities, genuine or otherwise, when she made her purchases in the Cleveland stores. The cash with which she paid probably came to her through her ability to make banks and bankers think she was a person to whom a loan, no matter how large, would be a good business investment, but when she dealt with the grocer, the butcher, the jeweler, or the house furnisher, she paid him in good coin of the realm, and paid him enormous sums. There is not a store in town that has not is story to tell."

It was said she bought several diamond rings at a time, and once purchased eight grand pianos from a piano store, making the gifts to her friends, or, more likely, to people she wanted to impress. Included in the many 1904 articles the flooded newspaper at the time of her arrest was an item that said, on one day, Mrs. Chadwick purchased 56 diamond rings as gifts.

Another story is she once took twelve young girls to Europe for the summer, and showered them with luxury. Or was it twenty young girls? Or merely four? It depends on who is doing the telling.

"Mrs. Chadwick was equally lavish in the matter of dress, and equally eccentric," the Sunday Tribune article went on. "A sealskin coat, reaching below the knees, would be a pretty present to give a dear friend. Mrs. Chadwick gave one to her cook."

The New York Sun (December 14, 1904) carried this item from Owatonna, Minnesota.

|

New York Sun, December 14, 1904

Owatonna, Minnesota, December 13 — Judge M. B. Chadwick of this city is a brother of Dr. Leroy Chadwick. Three years ago, Judge and Mrs. Chadwick accompanied a party that included all the Chadwick brothers on a European tour that lasted three months. All the expenses were paid by Mrs. Cassie Chadwick.

When the judge's daughter was married, Mrs. Chadwick sent a mahogany chest filled with valuable silver. The Owatonna Chadwicks never had any suspicion that the Cleveland woman's wealth had been obtained in any other than an honorable way.

|

|

There were four Chadwick brothers at the time. In addition to Dr. Leroy Chadwick and Judge Miles B. Chadwick, there were James. D. Chadwick, the Franklin, Pennsylvania, lawyer, and Bingham H. Chadwick, who lived in Jacksonville, Florida.

The Owatonna Chadwicks might not have been suspicious about Cassie, but the Pennsylvania Chadwicks would soon have reason to be concerned and to consider that they had footed at least part of the bill for the European trip: |

New York Daily Tribune, November 30, 1904

FRANKLIN, Pennsylvana, November 29 — A Franklin relaive of Mrs. Cassie L. Chadwick holds her notes for more than $9,000. The first note was given to James D. Chadwick, a brother-in-law, in 1901, and was for $2,000, the paper drawing interest at 7 per cent. The second was given to Mr. Chadwickk also. The amount was $7,200, on which Mrs. Chadwick atgreed to pay 8 per cent.

On the latter there was no surety, Mr. Chadwick having had explicit faith in the ability of his sister-in-law to pay back the money. Mr. Chadwick, who was one of the best known lawyers in this section, died late in 1902. A few years before the first loan, Mrs. Chadwick was here, and attempted to borrow $100,000 from the local banks, but she was unable to get it.

|

|

Mrs. Chadwick was slow to repay the loans, and the matter fell into the hands of F. W. Echols, vice-president of the Franklin Savings Bank. A story in he New York Sun (December 12, 1904) used a wonderful phrase to describe what Echols did. He "used methods that brought Mrs. Chadwick to terms."

Those methods were legal, and involved taking steps to have Cassie Chadwick declared bankrupt. "Mrs. Chadwick learned of this and in the first mail sent a check for $2,000," said the newspaper. "This was followed by further broken promises which compelled Mr. Echols once more to threaten proceedings. The result was the same: another check for $2,000. The second and last payment was made in September."

Echols said he would have exposed Mrs. Chadwick had she not made the payments.

Late in 1904, a less patient Brookline, Massachusetts man named Herbert D. Newton became very nervous about the money he had loaned Cassie Chadwick, and filed suit, claiming she owed him $190,800. Other creditors followed, and it soon became clear none of them had a chance of being repaid. Because of Cassie Chadwick, it would be a blue, blue Christmas for many people in 1904.

|

|

|

But let's not get ahead of ourselves. Her effort in 1901 to borrow $100,000 from a Pennsylvania bank was an indication Cassie Chadwick's spending wasn't being covered by the relatively small loans she'd been getting during her first four years of marriage when she also went through whatever money she brought to the marriage, plus the estate of her husband, who, for reasons unclear in every story I've read, made no effort to stop her. Instead, he apparently withdrew from the marriage, stopping short of filing for divorce. Perhaps she had him in one of her hypnotic trances. Or he didn't want the world to know what a fool he was. Often ill — perhaps with imagined ailments — Dr. Chadwick went on extended trips to Europe with his daughter, leaving his wife to do as she pleased.

In 1902, she launched the con that would make her famous, and may have done it with an incident that is sure to be included in her movie, should it ever be made. This would allow her to receive six-figure loans, which she'd need to remain Cleveland's biggest spender.

This particular incident, if it actually occurred according to legend, is an example of a problem facing anyone who sets out to make a movie about Cassie Chadwick. This incident is necessary to such a film, but likely will seem too tritely cinematic because we've already seen similar incidents in many films about con artists and thieves, and all of those scenes required viewers to suspend belief. For example, in real life, no one could pull off the stunt Pierce Brosnan pulled in "The Thomas Crown Affair." But Cassie Chadwick supposedly did something simpler, but equally outlandish, and when she was done, her reputation was golden, her credit rating A-1. Several bankers who should have known better were happy to loan her huge amounts of money, even though it must have seemed odd that someone who would claim her annual income was $750,000 a year needed such large loans so frequently. Odd or not, if she were willing to pay a relatively high interest rate and give them a bonus ...

But first she had to convince the right people she had the funds to cover those loans, and here's how she did it, as explained by an anonymous Cleveland lawyer to an unnamed Chicago Sunday Tribune reporter. What happened reportedly was later verified by many interested parties. The Tribune's story was published December 4, 1904, just when the world was wondering how a woman, who seemingly appeared out of nowhere seven years earlier, could have talked so many lawyers and bankers into loaning her huge amounts of money. What securities did she have to offer? And where did she get them? For Cassie Chadwick, these were easy problems to solve, given her forgery skill and her acting ability:

|

“Mrs. Chadwick began by consulting a prominent lawyer of this city [Cleveland] in regard to a contract in the form of a settlement between herself and a second party. She indicated in a general way the form of the agreement which was to be drawn up. The attorney was asked to prepare a draft of the instrument and to submit it to her for revision and final touches.

"When he submitted the contract to Mrs. Chadwick, she directed him to make various changes, and for the party of the second part she named Andrew Carnegie. The sum to be settled upon her by the multi-millionaire was no less than $7,000,000.

“Next Mrs. Chadwick requested the lawyer who had drawn up the settlement to accompany her to New York. There she was to obtain Mr. Carnegie’s signature and complete the transaction which was to make her the possessor of a great fortune. Attorney and client found themselves at the Holland House [Hotel] in due course, and thence they took a carriage to Mr. Carnegie’s home.

“When their destination was near, Mrs. Chadwick suggested to her lawyer that as the business yet to be done was of an intimate and personal nature, it might be well for him to wait in the carriage for her return. She entered the Carnegie residence and perhaps remained there twenty minutes. When she came out, it was with an air of triumph and satisfaction, and she told the Cleveland attorney that the settlement was signed and sealed and everything was concluded as she desired.

“In this matter there was no affectation of secrecy. In fact, Mrs. Chadwick’s lawyer gained the impression that she was proud of her alleged business relations with the iron king. Therefore, when the attorney came back to Cleveland, he spoke to some of his friends of the general nature of the remarkable transactions which he supposed himself to have witnessed. The story spread, or, at least, the import of it gained circulation enough to give many Clevelanders the impression that Mrs. Chadwick and Mr. Carnegie had business dealings on a large scale.

“In the light of denials by both parties that they have had any transactions whatever, the inference is plain that Mrs. Chadwick’s visit to the Carnegie home was intended for effect upon her attorney and through him upon her credit and financial standing in Cleveland.

“What happened during the twenty minutes she remained in Mr. Carnegie’s home and whether she met Mr. Carnegie at all only Mrs. Chadwick and possibly Mr. Carnegie’s servants can tell.”

|

|

In his chapter on Mrs. Chadwick, George Condon told his version of this incident, and also did not mention the name of the lawyer who accompanied Mrs. Chadwick that day, but had this to say about the young man:

"She had studied her man carefully and she knew he was the kind of person incapable of keeping a confidence; in a word, a blabbermouth." |

| * * * |

Who's her daddy?

You can imagine how the scene at the Carnegie house unfolded. A butler greeted Mrs. Chadwick, who said she was there to check on the references of a domestic who had applied for work at her home, and claimed she had worked previously at the Carnegie home.

Of course, the would-be domestic did not exist, but Mrs. Chadwick managed to engage the butler in conversation and perhaps talked to another member of Carnegie's household staff until a sufficient amount of time elapsed.

Then, wrote Condon, "Cassie thanked the butler, and as she departed, she pulled out a large brown envelope from underneath her coat. She came out to the carriage holding the envelope in such a way as to make it conspicuous.

'The young Cleveland lawyer was spellbound by this time, and losing the reticence which is the nature of good attorneys everywhere, he admitted his great curiosity over Cassie’s visit to the Carnegie house."

With faked reluctance, Cassie confided she was the illegitimate daughter of Andrew Carnegie, who'd been a bachelor until 1887, when he became a 51-year-old groom. Mrs. Chadwick swore the lawyer to secrecy, knowing he wouldn't keep his vow when he returned home.

In Condon's account, he implies no one should have believed her story in the first place because the idea "that Carnegie was the father of a middle-aged woman — Mrs. Chadwick was in her forties — was preposterous." Not really. Carnegie was 22 years old when Elizabeth Bigley was born. Yes, her story was preposterous for several reasons, but not because she was in her early 40s when she told it.

Turned out her selection of Andrew Carnegie as her make-believe father was a stroke of genius. He was a strange, very private billionaire who would have kept something like that a secret. He postponed marriage until 1887 because he'd promised to remain single as long as his mother was alive. He finally wed a year after her death. Bankers weren't about to ask him if he'd fathered a girl in 1857.

The secrecy essential to Mrs. Chadwick's lie made it easier to convince banks of her need for loans, since the cash in the documents she'd forged in Carnegie's name prevented easy access to his money. The embarrassment of Cassie Chadwick's existence — if her story were true — would be even greater around 1900 because Carnegie's wife gave him a legitimate daughter in 1897.

So within a few weeks of that 1902 trip to New York City, the word was all over Cleveland — Dr. Leroy Chadwick's wife was the daughter of Andrew Carnegie, and she was worth millions and millions of dollars. And this came from a very reliable source, or so people thought. |

| * * * |

Did it really happen?

The lawyer's name is no longer a secret — it's James Dillon — but whether the story is true or whether there really was a gullible young Cleveland lawyer named James Dillon are two questions that haven't been convincingly answered. However, both are generally accepted as truth by people who've written about Cassie Chadwick in the past 20 years.

I don't think James Dillon existed. Nor do I think she wanted to spread word that she was Andrew Carnegie's illegitimate daughter. Not yet. She was more interested in bankers knowing that for whatever reason, she was financially backed by one of the richest men in the country. And the bankers would find that out from one of the most trusted men in Cleveland — Iri Reynolds, secretary and treasurer of Cleveland's Wade Park Bank. (That's no typo — his name was Iri, not Ira as it is often written.)

Some eventually came to suspect that Reynolds was Mrs. Chadwick's secret partner in her scam, though he overwhelming feeling was he had acted naively and rather innocently in dealing with the woman and in responding to questions from bankers and lawyers who asked about the securities Mrs. Chadwick had handed him for safekeeping in a Wade Park Bank safe.

Reynolds was honorable to a fault. When Mrs. Chadwick gave him her Carnegie documents to be locked in a safe at his bank, she suggested he look at them, knowing he wouldn't. That would be a sign if mistrust. Most likely she told Reynolds she was Andrew Carnegie's daughter, but did it knowing Reynolds was not a gossip. If anything, he'd never repeat it to anyone, but the knowledge of the relationship would make him all the more convincing when he replied to bankers' questions about Mrs. Chadwick's ability to repay loans

(You may recall from Part 1 that a woman who'd worked for Mrs. Chadwick seemed sure her boss had more than a business relationship with Reynolds.)

|

Partner in crime?

If Mrs. Chadwick had a secret partner, and I believe she did, he was the New York City lawyer who prepared the papers to which she affixed forged signatures of Andrew Carnegie. I don't know how she paid this lawyer, or how much, but he had to be the person who handled inquiries from creditors who sought the location of slippery William Baldwin, almost certainly a make-believe New York City attorney Mrs. Chadwick claimed controlled the money she said she received twice a year from her mysterious accounts.

Ohio historian Amanda Wachowiak, in her article, "The Complicated Chadwick Affair," shares my skepticism about a naive Cleveland lawyer named Dillon, whose name appears nowhere in news stories about Cassie Chadwick in the early 1900s. All Mra. Chadwick had to do was convince Iri Reynolds that the package she brought back from New York was real. He would be her reliable source. So it was pointed out by the Chicago Sunday Tribune on December 11, 1904.

|

Chicago Sunday Tribune, December 11, 1904

No single act in her weird career illustrates more clearly Mrs. Chadwick's perspicuity and shrewdness than the manner in which she made Iri Reynolds believe that the package contained millions of dollars worth of securities, and induced him to sign an attest as to their value.

When Mrs. Chadwick deposited the package of securities with Mr. Reynolds, she told him she was the illegitimate daughter of Andrew Carnegie, and in that way accounted for the possession of the bulky package, saying:

"This package contains $5,000,000 worth of Caledonian railway bonds. Please take care of them for me and give me a receipt for the securities."

Mr. Reynolds wrote out the usual receipt for a package of securities and handed it to the woman.

Mrs. Chadwick glanced at the document for a moment and then handed it back, saying:

"Mr. Reynolds, I do not want such a receipt. I want you to state the value of the securities, so that in the event I should die, my heirs will know just what you have been intrusted with. I do not, of course, intend to use this in order to secure loans. You can see that, with these securities, it is unnecessary."

Then, at the dictation of Mrs. Chadwick, Iri Reynolds wrote out the attest, which, in brief, stated that Mrs. Chadwick had in the Wade Park Bank securities, unencumbered, to the amount of $5,000,000. The idea that Mrs. Chadwick was playing a shrewd game never entered the unsuspecting mind of banker Reynolds. As he has frequently said, Mrs. Chadwick had been introduced to him years ago by her husband as a woman of wealth; she had been of good customer of the bank for years, depositing big sums of money at different times.

He never for a moment realized that she might and would use the attest in the manner which she has done, and when he discovered that she was using his name in such a manner, he thought it might be all right, for he fully believed that the alleged securities in the package were worth the value she placed on them — namely: $5,000,000.

|

|

| With Iri Reynolds convinced, Cassie Chadwick entered the world of high finance, and within a couple of years destroyed one bank, caused runs at a few others, and had to talk one banker out of committing suicide after he showed up at her house, pulled out a gun and threatened to shoot himself. |

| |

| Cassie Chadwick, Part 4 |

| |

|

|