|

|

Part four:

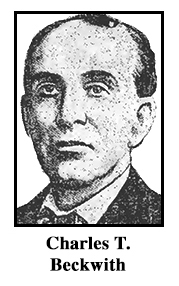

Cassie Chadwick's handling of Iri Reynolds was matched by the way she played the sixtyish president of the Citizens' National Bank of Oberlin, Ohio. Charles T. Beckwith came to rationalize his actions by convincing himself he was helping his bank as much as he hoped to help himself.

|

Chicago Sunday Tribune, December 11, 1904

It is not known how many small fish Mrs. Chadwick caught upon the lines she dangled in the sea of finance all over northern Ohio, eastern Pennsylvania and even in New York. The real story of her angling for millions has not yet been told. But C. T. Beckwith, president of the Citizens’ National Bank, was the first big fish she caught in her nets when she went after larger game.

Mrs. Chadwick’s first use of Beckwith was to employ him to negotiate a loan of $75,000 from the trustees of Oberlin College. Beckwith was successful and received a bonus of $5,000 in cash as his reward. The loan from Oberlin College was paid when it became due, and Mrs. Chadwick was raised high in Beckwith’s confidence.

Then Mrs. Chadwick began to dangle the bait before Beckwith himself. She admitted him to the secret of her birth — that is, she told him she was the daughter of Andrew Carnegie. She told him of her immense fortune — of her millions tied up on an estate, of the securities belonging to that estate held by Iri Reynolds as trustee. She told that Mr. Carnegie was going to transfer the stewardship of her millions. Beckwith should be the trustee. |

|

In time, Beckwith would confess to his bank's directors that Mrs. Chadwick promised he would be paid $10,000 a year as trustee of her estate, and his bank was to be paid a bonus of $40,000. He admitted he believed she was the illegitimate daughter of Andrew Carnegie, and that Carnegie turned  over to her an immense fortune. He believed so strongly in Mrs. Chadwick that he loaned her $240,000 of the bank's money, plus $102,000 of his own savings. The $240,000 was four times the capital stock of the bank, and the loan was illegal, given in secret, without Beckwith consulting the board of directors. over to her an immense fortune. He believed so strongly in Mrs. Chadwick that he loaned her $240,000 of the bank's money, plus $102,000 of his own savings. The $240,000 was four times the capital stock of the bank, and the loan was illegal, given in secret, without Beckwith consulting the board of directors.

He tried to convince himself the woman would make good on her promises, but as days went by, he became more and more nervous, and often visited Mrs. Chadwick at her home in Cleveland and at the Holland House Hotel in New York City, where she rented a suite by the year, so often did she visit.

Each Beckwith visit was futile. Mrs. Chadwick never ran out of excuses why she couldn't repay the loans just yet, and, later, why she couldn't let Beckwith see her securities, which were kept at a Cleveland bank in the care of Iri Reynolds.

When Beckwith confessed to his directors, he told an interesting story, parts of which were confirmed by others who dealt with Mrs. Chadwick. I'm surprised this story didn't trigger a wider investigation, because it seemed to me it proved she wasn't operating alone, though her associate most likely wasn't a full partner.

First, here's how Mrs. Chadwick explained to Beckwith and other victims how her "estate" worked: It was in the hands of three trustees, all New York City lawyers, she said. One of them was named William Baldwin, and it was through him, she claimed, that she received her money — $750,000 annually, in two payments during the year. |

Paging William Baldwin!

After repeated — and unsuccessful — attempts to contact Baldwin, Beckwith said he began to suspect the man didn't exist. He was akin to the fictitious George Kaplan in "North by Northwest," except no one ever mistook an innocent party for Baldwin and tried to kill him.

One of several frustrating failures in my online trip through Cassie Chadwick's scam is being unable to find any mention of how Beckwith or any other creditor — or lawyer — tried to contact Baldwin. They must have talked to someone, and it would almost have to be a person who answered a telephone in New York City. I think I know who that person was, but no one ever proved it. I'm not sure anyone ever tried.

The saga of Beckwith and the Citizen's National Bank of Oberlin played out like a movie script, without a happy ending. Yes, three people responsible for the bank's failure were arrested, but there was no good news to go along with the bad.

According to the Rochester (NY) Democrat & Chronicle (December 6, 1904), in a story most likely provided by an unnamed New York City or Cleveland newspaper, the precarious condition of the bank was discovered on July 1 by William B. Bedortha, the bank's attorney, who noticed large sums were missing, loaned without collateral security. He reported his findings to cashier Arthur B. Spear, who referred him to Beckwith, who'd been president of the bank for five years.

When confronted by Bedortha, Beckwith admitted what he had done, but swore Bedortha to secrecy, claiming he (Beckwith) would convince Mrs. Chadwick to repay the money loaned to her by the bank. Bedortha maintained his silence for awhile, but, on his own, contacted Mrs. Chadwick's lawyers, but had no more luck than Beckwith at having the loan repaid. That's what the Rochester story said, but the date — July 1 — seems too early in the year, and raises a big question of why Bedortha would give Beckwith more than four months to do what the lawyer knew couldn't be done — force Mrs. Chadwick to repay the loan.

Further, Bedortha, described as a young man, but with no age given, was dying. He couldn't afford to wait that long to tell the directors, though most stories say he did wait, and didn't inform the directors until mid-October or early November. (If the Rochester story is correct, it would have to be October 12, because Bedortha talked to the directors from his deathbed.)

Bedortha's death was just one of at least three over the next several months that would involve officials of the bank, and a lot of folks in Oberlin blamed those deaths on Cassie Chadwick. In addition, there were humiliating and infuriating events, though I'm uncertain of the order in which they occurred, and, in most cases, the dates.

The New York Herald (December 7, 1904) carried a story in which Colonel John W. Steele, one of the directors of Citizens National Bank, indicated he and the other directors were concerned about the bank's loan to Mrs. Chadwick before Bedortha's warning, and that's why two directors, named Randolph and Carter, went to New York City with Beckwith to meet with Mrs. Chadwick and her Manhattan lawyer, Edmund W. Powers. |

Liar, liar, pants on fire!

As Beckwith eventually would tell reporters, he and the two directors found Mrs. Chadwick at the Holland House Hotel, occupying a suite of five rooms, attended by two maids. There they were joined by Powers, who told them arrangements had all been completed to repay the loans — not only the one to the bank, but also the money from Beckwith's personal savings. This would be done the next day, said Powers, who suggested the directors might as well leave for home, which they did. Beckwith remained in New York City to receive the money. Yeah, right.

The next morning arrived, and poor Beckwith was given a convoluted story about the unexpected involvement of a Pittsburgh bank, which held the power of attorney blah blah blah, delaying payment. Back to Oberlin Beckwith went, empty handed.

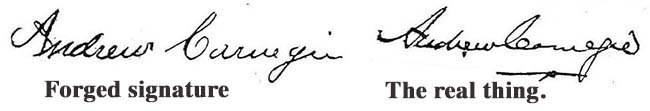

According to Colonel Steele, in the New York Herald story, Beckwith then prevailed upon Mrs. Chadwick to arrange for a lawyer to visit Oberlin. Both Steele and Beckwith say it was Powers who showed up to attest to the genuineness of the Carnegie signature. They say Powers presented himself as representing a New York trust company, something the lawyer denied when questioned about it in December.

It seems obvious — to me, anyway — that Powers must have been in on the scam, and since 1902 had fielded all inquiries about the mythical William Baldwin. For sure it was Powers who frequently assured people of Mrs. Chadwick's wealth, and had recently said she'd gifted her husband $2,500,000, and was still a millionaire in her own right. The man's nose must have been enormous.

By December, Beckwith was talking freely to anyone who would listen, trying to convince people that he may have been foolish, but he'd made honest mistakes in his financial dealings with Mrs. Chadwick. |

Chicago Sunday Tribune, December 4, 1904

“It was a little over two years ago when I first met Mrs. Chadwick. She came to this city to see me relative to making a loan. I do not believe there was a single thing about that meeting that made it different from hundreds of others. It was a conference on a straight business deal.

“She said she needed money and I thought from what she said that I was not assuming an unusual risk by letting her have it. You must remember that at that time I was dealing with her as a private citizen and not as the president of a bank. The first loan, I believe, was $5,000. It was paid when due. There were other loans, from my own resources, at different times. These were made quite frequently. At first, all of these were in small amounts, $5,000 or thereabouts. It was later that she came to me for greater sums. Do you think it at all strange that she gained my confidence? Is there anything unusual about it? Having business with her for months, I naturally looked upon her as all she claimed to be. All of the time her demands were growing heavier

.

“Before I knew it, she had borrowed a much larger sum than I supposed. Then my confidence was not shaken. Finally, I loaned her money belonging to the bank. That was my mistake. It was of the head and not of the heart, however. There is little to say after that. You know the rest. It has brought all this on me. Does anyone believe I would have deliberately entered into a transaction or a series of transactions that would have wrecked the bank?"

|

|

When Beckwith addressed the question of why a woman so wealthy was continually asking for loans, he mentioned her explanation about how she was paid from her trust — twice a year by a New York City lawyer named Baldwin. To Beckwith, at least, it made sense that she might need cash between payments, then use money from those payments to settle her loans. What wasn't explained, of course, is why the woman simply couldn't adjust her spending to avoid losing so much money in interest and bonuses to her creditors. Beckwith and her other creditors wouldn't admit it, but they were pleased to be dealing with someone willing to do just that. Beckwith may have trusted the woman, but he had to believe she was more than a little foolish.

So was Beckwith, who was too easily impressed by what he saw as the woman's wealth.

“I have seen three chests full of jewels owned by Mrs. Chadwick," he told reporters. "There were diamonds worth a king’s ransom. She would have these stones in little trays made to fit into different compartments in the trunks. Apparently she had a great delight in displaying these. She would hold them in her hand and fondle them. Mrs. Chadwick was an expert on gems. She would pick out a white diamond or an emerald or a ruby and tell at a glance how many thousands of dollars it was worth. This was only one more of her many remarkable traits. She had one necklace, a string of pearls, that was valued at $15,000. This was purchased abroad. Her jewels alone must have been worth half a million dollars."

As things turned out, few things Mrs. Chadwick had purchased were worth the prices she was willing to pay. |

Beckwith threatens suicide

After the directors were alerted to the $240,000 loan made from bank funds, they pressured Beckwith, whose behavior became increasingly pathetic: |

Chicago Sunday Tribune, December 11, 1904

One tragic incident related by Beckwith in the written confession concerns one of the visits of President Beckwith, Cashier Spear and Judge Albaugh to the Cleveland home of Mrs. Chadwick. The two bankers pleaded for money. Mrs. Chadwick made more promises.

Mr. Beckwith was aroused to anger, and when he saw the hopelessness of it all, he threatened to commit suicide. He drew a revolver. Mrs. Chadwick cried that “all would be lost” if the banker carried out his threat. The result was that the bankers again relied upon promises. |

|

Judge Albaugh was John Albaugh of Canton, Ohio, one of several lawyers hired by Mrs. Chadwick over the years. I found it interesting that it was Albaugh, not Powers or the other New York City attorney, Philip Carpenter, who represented Mrs. Chadwick during a meeting in New York over a lawsuit filed by another creditor. That meeting was a week after another pitiful attempt by Beckwith to prompt Mrs. Chadwick to make good on a promise. This time Beckwith visited her by himself at her Cleveland home on November 23, 1904, the day before Thanksgiving.

Later he went public with what happened that night: |

New York Herald, November 30, 1904

"Mrs. Chadwick," Beckwith said to her. "I do not care for myself. I can wait for the money that I loaned you out of my own pocket. It is not my fortune which I am trying to retrieve, but my honor. Surely there are ways by which you can raise money. Surely you can pay back the loans made by the bank."

Her answer was again and again, "I cannot pay now."

The old banker fell on his knees and pleaded with her, he later told the bank's directors, but to no avail. When he arose, he fell in a faint, and it was necessary for him to remain at the Chadwick home overnight. |

|

At some point that fall, Mrs. Chadwick gave Beckwith a check for $50,000, but it bounced. She then sent him two checks for $25,000 each, but called the next day to tell him not to cash them. He no longer had any doubt Mrs. Chadwick was a thief.

But Beckwith and Oberlin's Citizens' National Bank weren't the only problems facing Mrs. Chadwick, who'd been slapped with a lawsuit by Herbert D. Newton of Brookline, Massachusetts, a financier who'd loaned her money, and now claimed she owed him $190,800. Within days of Beckwith's last visit, Mrs. Chadwick was on her way to Boston, and from there would go to her home away from home, the Holland House Hotel in Manhattan.

Meanwhile, Beckwith and cashier Arthur B. Spear would be arrested close to midnight on Sunday, December 4, for violations of banking laws, though Beckwith's self-inflicted punishment would be worse than anything a court could accomplish. On February 5, 1905, Beckwith passed away at home after several days of refusing to eat.

Mrs. Chadwick expressed some regret at his passing, but expressed no feeling about the death of the man's bank, perhaps believing it was entirely his fault for giving her money the bank didn't have.

Early in March, Spear, only 22 years old, received a seven-year sentence, but was expected to be released after serving five years.

As all main attractions go, the Cleveland trial of Cassie Chadwick was saved for last, |

|

|

While the crash of the Citizens' National Bank in Oberlin and its effect on its president, Charles T. Beckwith, made for the biggest human interest story of the Cassie Chadwick banking scandal, it was the suit filed by Herbert E. Newton, the Brookline, Massachusetts, financier that sounded the alert there was something fishy about the free-spending woman from Cleveland.

And as soon as Newton's suit became widely known, so did a rumor that had been circulating in northern Ohio for years — that Mrs. Cassie L. Chadwick, in a previous life, had been Lydia Devere, the clairvoyant forger who'd spent time in the Ohio Penitentiary. Well, this was more than a rumor to several people, but their warnings about the woman were ignored until Mrs. Chadwick ran into legal problems.

You may recall that on the marriage license it was stated Cassie L. Hoover was born in New York State. That was an attempt to separate herself from Lydia Devere, whose Canadian birth and real name (Elizabeth Bigley) were well known to authorities.

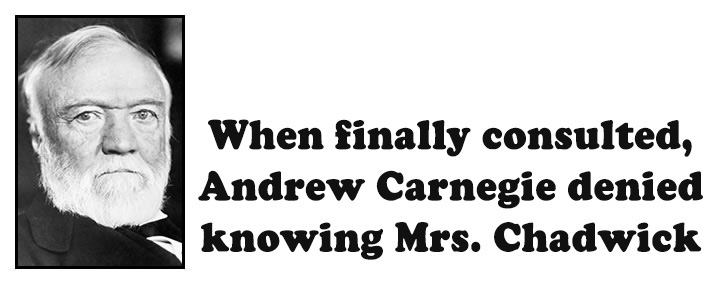

Also, Andrew Carnegie finally became aware that his signature appeared on notes held by Mrs. Cassie Chadwick of Cleveland, who'd told people she was his illegitimate daughter. Carnegie said he didn't know the woman and certainly had not signed any documents on her behalf. However, he was flattered that his signature — even when forged — was worth more than a million dollars. |

Mrs. Chadwick had help from God

While Mrs. Chadwick hadn't had luck in being accepted by the right people in Cleveland, she knew how to take advantage of her location. A little more than a mile from her home was Euclid Avenue Baptist Church, attended by John D. Rockefeller, whose home also was about a mile from the Chadwicks.

Mrs. Chadwick wasn't a churchgoer, but that didn't stop her from visiting Euclid Avenue Baptist Church to talk to the pastor, the Rev. Charles A. Eaton, telling him she was seeking financial advice, specifically, where she could raise money. She showed him an attest signed by Iri Reynolds of the Wade Park Bank, saying he held $5,000,000 worth of her securities.

The Rev. Eaton must have been taken aback, but he gave her the obvious reply: She should seek a loan from Cleveland bankers. She managed to convince him she had a good reason not to do that. She didn't want bankers in her hometown to be aware of her temporary financial embarrassment. I'm sure she didn't admit she already knew the Rev. Eaton had a well-connected brother who was a Boston lawyer.

Long story short, the pastor agreed to contact his brother, John E. Eaton, who soon received a phony note for $500,000 bearing Andrew Carnegie's signature, plus a list of securities. As a favor to his brother, lawyer Eaton set out to connect Mrs. Chadwick with a banker. She wanted to borrow $200,000, but was turned down.

Next, lawyer Eaton turned to one of his clients:

|

Chicago Sunday Tribune, December 11, 1904

Herbert E. Newton, the Brookline, Massachusetts, financier, was Mrs. Chadwick’s next victim. The woman of mythical millions was introduced by John E. Eaton, an attorney who was a relative of the Rev. Charles A. Eaton, pastor of Euclid Avenue Baptist Church of Cleveland, attended by John D. Rockefeller. Newton met Mrs. Chadwick in Boston.

“Mrs. Chadwick came to Boston last April,” said Mr. Newton. “She was sent here by the Rev. Charles A. Eaton, pastor of the Euclid Avenue Baptist Church of Cleveland. Dr. Eaton had been appealed to by her as a woman in distress, and had acted as a pastor to help her out. She came to the office of Mr. John E. Eaton, in the Tremont Building, where Mr. Eaton is a member of the law firm of Eaton, McKnight & Carver. From Dr. Eaton of Cleveland, she carried his instructions to give her assistance, if, after examination of her securities, her statements could be verified.

“It was in Mr. Eaton’s office in the Tremont Building that Mr. John E. Eaton introduced

Mrs. Chadwick to me. At this meeting, Mrs. Chadwick showed me the securities she held, and among them was the $500,000 note signed ‘Andrew Carnegie,’ and also the certificate signed by Iri Reynolds, which stated that he had in his possession $5,000,000 in securities belonging to Mrs. Chadwick. We communicated with the Rev. Dr. Eaton, and he confirmed the signature of Mr. Iri Reynolds. The signature on the $500,000 Carnegie note was never verified beyond Mrs. Chadwick’s own statements.”

Newton went to Cleveland and interviewed Iri Reynolds, who “personally acknowledged his signature to the certificate of securities, and the strictest inquiry showed that Mr. Reynolds was supposed to enjoy in the city of Cleveland the reputation of being a man of the highest integrity and honor.

“Upon these representations, I decided to help Mrs. Chadwick and agreed to let her have $14,000. I paid the money to John E. Eaton, and he gave Mrs. Chadwick his check. After this first loan, I negotiated with Mrs. Chadwick myself and made the loans under which she became so heavily indebted to me.”

|

|

| While the bank directors in Oberlin tried to keep their problem quiet after lawyer Bedortha's discovery in July, word reached Newton that there were problems with Mrs. Chadwick's other loans. Just the fact she had those loans and came to him for more money made Newton nervous, and, in November, he filed suit against the woman. |

Somewhere beyond the sea

So where was Cassie Chadwick's husband while she was under suspicion, squirreled away in a New York City hotel suite, being watched by Secret Service men? Dr. Chadwick and his daughter were in Europe, and would remain there for weeks even after his wife was arrested. Those investigating his wife's financial dealings had plenty of questions for Dr. Chadwick, but none of them concerned that $2,500,000 he supposedly received from his wife. Everyone knew it didn't exist, because if it did, Dr. Chadwick's two $25,000 checks to Herbert B. Newton, the troublesome Brookline, Massachusetts financier, wouldn't have bounced. (The doctor's excuse: His wife was supposed to cover them. Truth was, Dr. Chadwick was broke.)

There was much dispute over the actual amount of money Newton had loaned Mrs. Chadwick. Her lawyer, Edmund Powers said Newton arrived at $190,800 by adding in a bonus and the interest on the loan. Newton claimed he'd actually given the woman $190,800.

Karen Abbott, in "The High Priestess of Fraudulent Finance," wrote that Newton loaned Mrs. Chadwick $79,000 from his business, and wrote her a personal check for $25,000 — $104,000. In return, she signed a promissory note for $190,800 without questioning the outrageous interest, which is understandable if she had no intention of paying him anything.

Mrs. Chadwick would claim during a bankruptcy hearing in March, 1905, that she had received $78,000 from Newton, and what he was suing for included $112,800 in interest and a bonus.

Once Newton took action to force the woman to pay, several other creditors jumped into the act, though the other suits filed were by merchants owed much smaller amounts of money. This aroused much public interest, and for several days after Mrs. Chadwick arrived in New York City in late November, she was a virtual prisoner at the Holland House Hotel, which attracted reporters and other curious people, much to the dismay of hotel management, as well as Mrs. Chadwick.

On November 30, Newton's attorneys announced a settlement had been reached with Mrs. Chadwick, and the next day newspapers indicated she had resolved one of her problems, but, of course, she hadn't. What she told Newton's lawyers was her version of, "The check is in the mail." Like Beckwith, Newton and his lawyers finally realized the woman had no intention of making good on her promises. Her arrest was inevitable, and she already was behind bars when this news broke in Ohio: |

New York Evening World, December 12, 1904

CLEVELAND, December 12 — The Grand Jury of Cuyahoga County returned two indictments against Mrs. Cassie L. Chadwick this afternoon.

Each indictment contains two counts, one of forgery and one of uttering forged paper. One of the indictments related to the Carnegie note of $500,000, and the other to the note for $250,000, used to borrow money at the Oberlin Bank.

Additional arrests in the case of Mrs. Chadwick that will bring out a story of conspiracy as sensational as anything that thus far has be exposed are anticipated. Five persons in various parts of the United States are under the unremitting surveillance of Secret Service detectives.

These person are all suspected of having guilty knowledge of the swindling schemes of Mrs. Chadwick. It is believed at least one of them is a woman. Their every action during the period of Mrs. Chadwick's gigantic operations is being investigated.

|

|

Mrs. Chadwick also was indicted by a federal grand jury, and United States Attorney John J. Sullivan, who would prosecute the case against her, was certain some prominent persons had shared in the proceeds of Mrs. Chadwick’s enormous loans.

One person closely watched was lawyer Edmund W. Powers, though, as far as I know, he was never arrested. Not that it would have done much good, even if Powers were Mrs. Chadwick's secret partner. Though only 49 when the Chadwick case broke, Powers' health soon failed, and within two years he retired from the law, blind and an invalid in the care of his wife at the home in Putnam County, near Oscawana Lake, New York. In 1908, Edmund Powers died.

Speculation over the identities of others who might be arrested for their involvement in Mrs. Chadwick's scam was interrupted in mid-December by the news Herbert Newton and Charles Beckwith weren't the biggest contributors to the woman's gofundme scheme. That title belonged to a Pittsburgh business man who was quite a schemer himself. |

|

|

Questions, questions, question ... there were a lot of them when Cassie Chadwick's scam was exposed and she was placed under arrest. The biggest questions were: How did she convince bankers to give her so many loans? How much money did she have? And where was she hiding it?

I think the first question was answered by bank president Charles T. Beckwith of Oberlin after he confessed his financial involvement with Mrs. Chadwick to his board of directors and echoed his mea culpa to any reporter willing to listen. Beckwith probably felt worse when he learned most bankers who met the woman had turned her down when she asked for loans.

No doubt, those men who agreed to give her huge amounts of money were swayed by the rather vague assurance of Iri Reynolds, a much respected and trusted Cleveland bank official, who, unfortunately for him, also was too trusting and respectful, believing the word of a woman who just happened to be married to a man who'd been Reynolds' friend most of his life. All Reynolds was actually telling other bankers is he was holding securities that Mrs. Chadwick claimed were worth several million dollars. He never said he'd made an attempt to verify Andrew Carnegie's signature on those documents.

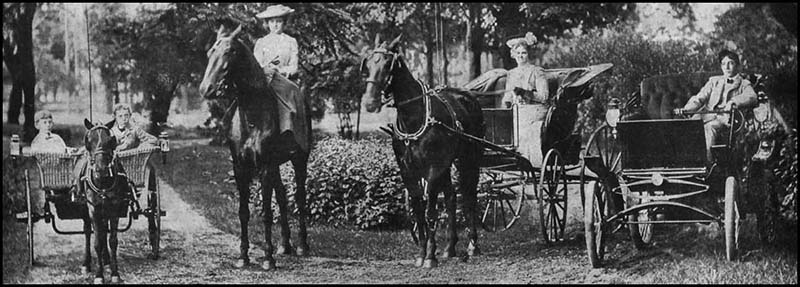

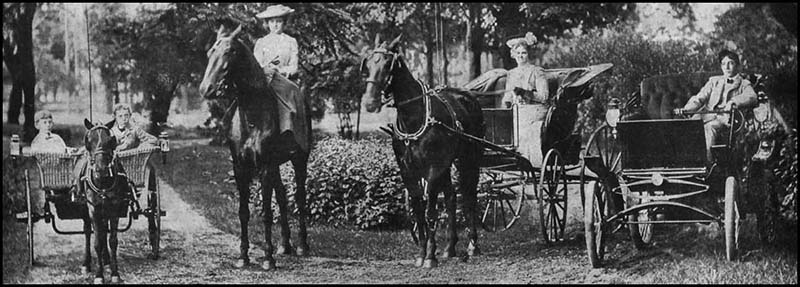

When they were finally examined in mid-December, 1904, the results were shocking, humiliating, and, to some, amusing. There were two documents — one a note promising $5,000,000, the other a trust supposedly worth more than twice that amount — backed by a forged signature of Andrew Carnegie. Both documents, of course, were worthless, though I imagine they'd fetch a good price today among collectors of forged signatures. The only thing worth any money was a note for $1,800 from Emily and Daniel Pine, payable to Cassie L. Chadwick, and a mortgage to secure the same. Emily Pine was one of Cassie Chadwick's sisters; she and her husband also lived in Cleveland and had two sons, who appear in a wonderful photo at the bottom of this page that shows Mrs. Chadwick, her son, Emil, and her stepdaughter, Mary. The boys are in horse-drawn cart, Mary is on horseback, Mrs. Chadwick in a horse-drawn wagon, and Emil in an automobile. The good life on display in the early 1900s.

The discovery of the true value of Mrs. Chadwick's securities convinced Herbert D. Newton and the directors of Citizens' National Bank in Oberlin there was no chance they'd be repaid. (It was estimated that, at best, they'd receive 16 mills on the dollar, or less than two cents.)

Because Newton had met Mrs. Chadwick through the pastor of John D. Rockefeller's church, the Massachusetts financier had the silly idea Rockefeller would cough up $190,800 out of some weird sense of responsibility. As far as I know, Rockefeller wasn't moved by Newton's foolishness.

Carnegie did help certain depositors of the Oberlin bank, reimbursing college students and citizens who could ill afford to lose the money they had entrusted to the bank.

|

A Friend indeed

It wasn't until Cassie Chadwick's bubble had burst in early December, 1904, that it was revealed she had landed an even bigger fish in Pittsburgh, a businessman named James W. Friend. Of her "victims," Friend was the one who could most afford to lose a lot of money, and at the same time was the least likely to complain about it, especially given his motivation in loaning Mrs. Chadwick $800,000 — or $798,200 to be precise.

At first, Mrs. Chadwick denied any dealings with Friend, who simply refused to comment one way or the other. What was revealed — and speculated upon — over the next few years gave reason to believe Mrs. Chadwick may have borrowed $2,000,000 or more during her marriage to Dr. Leroy S. Chadwick, whose involvement in her scheme became more and more suspect. Iri Reynolds said the doctor knew everything about his wife's dealings, but Dr. Chadwick, like Sgt. Schultz of "Hogan's Heroes," kept repeating, "I know nothing! know nothing!" and when his wife was hauled off to jail, he and his daughter remained in Europe, traveling from Paris to Brussels to Berlin, before finally sailing for the United States in late December.

Of all Mrs. Chadwick's dealings, those with Friend may be the most interesting. It appears they were trying to outplay each other, and while I have to believe he was suspicious about her Carnegie-supported "securities," he was willing to take a chance they were genuine, because that might give him an opportunity to grab millions of Carnegie's dollars should his illegitimate daughter fail to repay her loans. |

New York Press, February 7, 1905

PITTSBURGH, February 6 — A thrill of vindication ran up and down the spine of newspaper Pittsburgh this evening when news came from Cleveland that the official list of the creditors of Cassie L. Chadwick had been handed down and that among them appeared the name of James W. Friend of Pittsburgh. The amount was not made public, but it is believed to be about $800,000.

It was reported several months ago that James W. Friend of Pittsburgh was the man who had acted as banker for Mrs. Chadwick in Pittsburgh and that she had borrowed large amounts from him. This was investigated and found to be correct, so far as circumstantial evidence went, but there came a storm of denial, not from Mr. Friend, who until this day has refused to see a newspaper man, but from those in his employ and associated in business with him.

They denied loudly and often that Mr. Friend had lent any money to Mrs. Chadwick, and they got her to send out an interview from her cell in Cleveland in which she said she had not borrowed any money from Mr. Friend.

This evening there comes out what appears to be the real story of grab as practiced by Cassie Chadwick on the careful Pittsburgh banker.

In the spring of 1902, Mrs. Chadwick came to Pittsburgh with her box of paper and did what no business man has ever been able to do. She borrowed $300,000 from James W. Friend. The time was one year and the interest was to be paid quarterly.

This was done and so promptly that Mrs. Chadwick soon had a good credit with the Pittsburgh banker, and when, at the end of the year, she said she needed the $300,000 and would like to have it another year at the same rate, she was informed she could have it, and the papers were drawn up for another year.

Not long after that, Mrs. Chadwick found she needed $500,000 more and promptly wired Mr. Friend. For years, Friend had been looking for a chance at his old enemy, [Andrew] Carnegie, and here he had it. His name, or what was passing as his signature, was at the foot of the securities held by the woman. So she got the $500,000,, which made a grand total of $800,000.

Mrs. Chadwick did not take any paper on the last trip, either. It is said by those who know of the deal that she took nice new bills — great stacks of them — in a new satchel and carried them in her lap to Cleveland where she dumped the $500,000 into a bank there on the same day. She had set forth from Cleveland at daybreak and in nine hours she returned there with $500,000 she got from Mr. Friend.

|

|

It wasn't quite that simple. Actually, there were six different loans over a year that totaled $798,200, and while the stories about the dealings between Mrs. Chadwick and Friend said the man had been duped, I believe he was simply gambling that she might have been telling the truth about her securities, but that she'd be unable to repay the loans, and he'd come into possession of all the millions promised by Carnegie.

Friend and his partner, Frank N. Hoffstot, had operated in similar fashion earlier with William C. Jutte, a millionaire coal operator who needed loans along the way, and when Jutte couldn't repay one of them on time, Friend and Hoffstot seized the man's estate estimated to be worth several million dollars. Jutte responded by killing himself in an Atlantic City hotel on May 25, 1905. He'd tried once before, in 1901, and even though he shot himself in the head that time, he survived. The second time he shot himself in the chest. His widow would involve Cassie Chadwick in an unsuccessful attempt to recover what was left of her husband's fortune. |

The great escape

But that was two years down the road. Let's return to Cassie Chadwick's last days in New York, and what became known as her wild ride. It came six days after an equally wild — and successful — attempt to ditch reporters and obnoxiously curious people who had followed her to a lawyer's Wall Street office. |

New York Evening World, December 2, 1904

While a throng of more than a thousand bankers and brokers, clerks and messenger boys surged about the Central Trust Company Building at 54 Wall Street, struggling and pushing in the hope of getting a glimpse of Mrs. Cassie L. Chadwick, the heroine of high finance, who had gone to the law offices of Butler, Notman, Joline & Mynderse, this remarkable woman made her escape by a rear window. |

|

That window was on the seventh floor and gave her access to a fire-escape to an extension roof. Then she crossed the roof and walked along what the newspaper described as "a perilous ledge" until she reached a rear window of the adjoining building at 56 Wall Street. This building had a passage that let Mrs. Chadwick exit a block away on Pine Street, where she had arranged for a cab to pick her up. She escaped unseen and returned to the Holland House. (Two years later Evelyn Nesbit Thaw would make a similar escape from the press when she visited her lawyer the day after her husband shot and killed Stanford White.)

A few days later, Mrs. Chadwick once more tried to escape reporters and the Secret Service agents who had been assigned to watch her. |

New York Tribune, December 8, 1904

MRS. CHADWICK’S WILD RIDE

Mrs. Chadwick left the New Amsterdam Hotel at 2:15 p.m. Before she went downstairs, a coach had been drive to the side entrance. She hurried into the carriage, accompanied by her son, Emil, and maid, Freda. Word that she was going had been spread among the newspaper men, and they were in carriages waiting for her departure, to follow and learn whither she went. Mrs. Chadwick evidently saw the carriages. There were eight of them.

“Drive fast,” she told her driver, “and if we are arrested for speeding, I will pay the fine.”

As she had at least one block start from the cab of her foremost pursuer, it was not long before her horse showed a clean pair of heels to every pursuing vehicle, and for close on half an hour things went very much her own way.

At a furious pace her carriage was driven up Fourth Avenue to Twenty-Seventh Street, west in the cross street to Madison Avenue, up to Twenty-Ninth Street, and then clear past the Hotel Breslin, at Twenty-Ninth Street and Broadway. Without even slacking speed, her carriage went west to Sixth Avenue, and south in that thoroughfare to Twenty-Sixth Street. It then turned east again to Broadway, and up Broadway to Twenty-Ninth Street, where it was turned to the side entrance of the Breslin.

Mrs. Chadwick then alighted and hurried to her rooms, having secretly engaged a suite in advance. Instead of five minutes, the journey occupied more than half an hour.

|

|

| About three hours later, Mrs. Chadwick was arrested, charged by the government with aiding and abetting a bank official in misapplying $12,500 from the Citizens' National Bank of Oberlin, Ohio. By the time she went to trial in March, she would face 16 separate charges. |

New York Tribune, December 8, 1904

A dramatic scene occurred in the woman's room when officials announced to Mrs. Chadwick that she was under arrest. It was about 6:15 p.m. when United States Marshall William A. Henkel, his deputies and Secret Service Agent William J. Flynn arrived at the hotel, ascending at once to the woman's apartments.

Mrs. Chadwick occupies a suite of four rooms on the seventh floor, overlooking a corner at Broadway and Twenty-Nine Street. Marshal Henkel entered without knocking, and found the woman in bed. Politely doffing his hat, he advanced to her bedside and said:

"Madam, I am United States Marshal Henkel, and have an unpleasant duty to perform. I am obliged to serve a warrant for your arrest, issue by the United States Commissioner [John A.] Shields at the instance of the federal authorities of Ohio."

Scarcely had he uttered the words than Mrs. Chadwick's maid, who, with her son, Emil, was in the room, lapsed into hysterics, sobbing and calling her mistress repeatedly by name. Although palpably nervous, Mrs. Chadwick continued, after a fashion, to maintain her composure.

"I am very nervous and ill," she objected. "What shall I do? I certainly am unable to get up."

"In that case," replied the marshal, "I shall be obliged to remain here and keep you under surveillance. You will realize that, unpleasant as this is for both of us, you are a prisoner, and I have no right to leave you here alone. I will do everything I can," he added, "to relieve you of annoyance."

|

|

Contrary to what some have written, Cassie Chadwick wasn't wearing a money belt containing $100,000 in cash when she was arrested. The whereabouts of her money remained an unsolved mystery, though it was suspected she may have used her son, Emil Hoover, then about 19 years old, to transport cash and jewels to Ohio before her arrest, but that was never proven.

Mrs. Chadwick spent her first night as a prisoner at the Hotel Breslin, then was arraigned the next morning before U. S. Commissioner John A. Shields, then taken to the Tombs, where she remained until the evening of December 13 when she boarded a train for Cleveland, arriving there shortly after 11 a.m. the next day.

One of the strange things Mrs. Chadwick did when she was booked at the Tombs was to say she was 51 years old, adding four years to her actual age at the time. No one seemed to notice what this did to her claim about being Andrew Carnegie's daughter. If she really were 51 years old in 1904, that would have made Carnegie 17 years old when she was conceived. Possible, of course, but even more unlikely than before.

She may have realized the problem during her trip back to Cleveland, because when she was being booked at the Cuyahoga County jail, she claimed she was 38 years old.

When she went to prison the first time (as Lydia Devere), she subtracted six years from her real age and told penitentiary officials she was 28 years old. Zsa Zsa Gabor had nothing on Cassie Chadwick. |

One in jail, the other at sea

Cassie Chadwick chose to remain in the Tombs for five days. “Let me make it plain why I do no seek bail," she told reporters. "It is not because I cannot get it, for only today I received a special delivery letter from one of the wealthiest men in the country, who has known me since I was twelve years old. In this letter he assured me that despite the penalty of publicity, he would sign my bail bonds for any amount. I shall refuse his kind offer, for while I am in jail I am free from the annoyance of curious people.”

Near her, in a cell in the same corridor of the jail, was 21-year-old actress-dancer Nan Patterson, whose trial for the murder of bookmaker Caesar Young was sharing headlines with the Cassie Chadwick scandal. Ms. Patterson was a newlywed, but that didn't prevent her from having an affair with Young, who also was married — until he took a carriage ride with the performer and wound up dead of a gunshot.

After one hung jury, Patterson was found not guilty in her second trial, but while she regained her freedom, she failed too cash in on her notoriety, and had a lackluster career. Young's killer was never caught; well, most observers thought the killer had been caught, but was let go by a jury perhaps swayed by the defendant's good looks.

Meanwhile, attention shifted momentarily from Cassie Chadwick to her doctor-husband, who remained vague about when he and his daughter would return from Europe.

Iri Reynolds and Charles T. Beckwith both insisted Dr. Chadwick was well aware of his wife's con game, but the doctor continued to make denials, though on December 22 a Cuyahoga County grand jury indicted him along with his wife on a forgery charge. By then Dr. Chadwick was headed home on the steamer Pretoria, expected to reach New York City on New Year's Eve.

The Pretoria made it to New York on schedule; Dr. Chadwick, accompanied by the Cuyahoga County sheriff, got on a train to Cleveland, and Mary Chadwick, the doctor's daughter, headed for Florida to live indefinitely with her uncle, Bingham Chadwick.

Dr. Chadwick arrived in Cleveland the next morning, on New Year's Day, and spent 90 minutes at the county jail visiting his wife: |

New York Times, January 2, 1905

CLEVELAND, January 1 — “Trust me! Trust me!” cried Mrs. Chadwick to her husband today as she clung to him in the woman’s ward of the Cuyahoga Jail and wept convulsively. “Don’t believe these stories which the newspapers have been printing about me,” she said. “They are lies, every one of them. I have done nothing wrong. Believe me; trust me; everything will come out all right in the end, and it will be seen that I have been guilty of none of these things the public charge me with. Don’t think I deceive you; I will tell you the truth, and I tell you that all these reports are lies — lies.”

“I can only hope so,” was the husband’s answer. “I have trusted you, and it is hard to believe anything; my mind is so confused. This has all been such a terrible shock, and I don’t understand any of it. I want time to think of it. I do not say I won’t trust you; only give me time to collect my thoughts. I am not the judge. I can only hope that everything will come out all right, as you say.”

The meeting of Dr. Leroy S. Chadwick and his imprisoned wife, the first they they have had since the woman’s troubles began, took place a few hours after Dr. Chadwick’s arrival from New York.

Sheriff Barry, in whose company Dr. Chadwick was on the trip, chose to come to Cleveland over the Pennsylvania Road. The train arrived in Cleveland at 7:30 this morning. The sheriff and Dr. Chadwick were quickly driven to the county jail, where Dr. Chadwick was registered as a man against whom the law has suspicion, but this was not made a part of the records at once. A bond provided Saturday evening by Attorney Virgil P. Kline and Attorney Dawley was ready at the jail on the arrival of Dr. Chadwick, and he was soon released.

After the preliminaries in the sheriff’s office, Dr. Chadwick was escorted by Sheriff Barry to the fourth floor of the woman’s ward, where his wife is held a prisoner. The meeting between the two was pathetic in the extreme. Mrs. Chadwick arose when she heard the steps in the corridor, and fell into her husband’s arms when she recognized him. Both broke down and wept convulsively for several minutes, while clinging to each other, the sheriff attempting meanwhile to console them.

The two then sat down for a talk that continued for an hour and a half. There were pleadings and partial responses. Dr. Chadwick has lost his all in the operations of his wife, and the large independent fortune of his only child has been swept away — sufficient reason, it would seem, for some show of hardness on his part. Mrs. Chadwick tried to imbue him with the thought of her innocence of any wrongdoing.

His only response to these pleas was, “I hope so.”

The wife told her story, interspersed by violent fits of weeping, in which at times Dr. Chadwick joined. There were no apparent evasions, but there was the constant cry of “Trust me, trust me,” on the part of the woman.

|

|

Later, Dr. Chadwick said, “All this trouble has come upon me with such suddenness that I am almost crushed. Of course, I am not guilty of any wrongdoing. For thirty-five years I have made Cleveland my home, and this is the first time there has been any taint on my name. It is too terrible. Even my home has been taken from me, and, if all reports are true, I am a penniless pauper.”

For the doctor there was some good news mixed with the bad. While his house had indeed been taken possession of for the benefit of Mrs. Chadwick’s creditors, lawyers decided Dr. Chadwick cannot be barred from its use. For a little while, anyway. |

| |

|

|

Happy days in Cleveland (though no one is smiling). Left-to-right: The two sons of Emily and Daniel Pine; the boys were Cassie Chadwick's nephews. That's Mary Chadwick on horseback; the daughter of Dr. Leroy S. Chadwick was about 18 when this photo was taken, the same age as Emil Hoover, Cassie Chadwick's son, who's in the automobile at the right. Between the two teenagers is Cassie Chadwick, aka Lydia Devere and many other aliases, who was born Elizabeth Bigley. |

|

|

It seemed certain Cassie Chadwick was headed back to prison, and while her husband was under indictment, he kept insisting he'd done nothing wrong. He was lucky enough to be spared a trial, though his humiliation might have been punishment enough.

Until Mrs. Chadwick went to trial, she remained confined to the Cuyahoga County jail, claiming it was her choice because she could have been out on bail if she wanted. At the jail, she had an interesting visitor who, perhaps jokingly, suggested the con woman might have an interesting career move in her future.

|

New York Morning Telegraph, February 8, 1905

Grace Cameron, the actress who has just returned from a Western tour and is this week playing an engagement at Keeney's Theatre, Brooklyn, is telling all her friends how she broke into the county jail at Cleveland last Saturday and had a chat with the Duchess of Ducats, Mrs. Cassie L. Chadwick.

Miss Cameron and Mrs. Chadwick have long been friends, and through the intervention of a Cleveland attorney, Peter Quigley, Sheriff Mulhern was prevailed upon to arrange a meeting between the two women in Mrs. Chadwick's cell for two hours. |

|

The story went on to say they talked of the decline of the drama, Parisian gowns, and how to get rich quick. Miss Cameron ate with Mrs. Cameron; the meal was delivered from a nearby hotel.

When she left, Miss Cameron kissed Mrs. Chadwick on the forehead and said she might be able to get her a job on the vaudeville stage doing some high finance kicking or something of that sort when her legal problems were all over. When she left, Miss Cameron kissed Mrs. Chadwick on the forehead and said she might be able to get her a job on the vaudeville stage doing some high finance kicking or something of that sort when her legal problems were all over.

Mrs. Chadwick responded with a wan smile, probably thinking such an offer, which wasn't as far-fetched as it seemed, would have been more up her alley back in her Lydia Devere days.

Miss Cameron had trained to be an opera singer, and was featured with the Bostonians, a comic opera company, before switching to vaudeville, where she was a big star for many years, kind of a forerunner to Fanny Brice. (While Brice enjoyed her biggest success on radio as "Baby Snooks," Ms. Cameron's biggest hit was "Little Dolly Dimples." You can hear her perform a song from that show on YouTube.

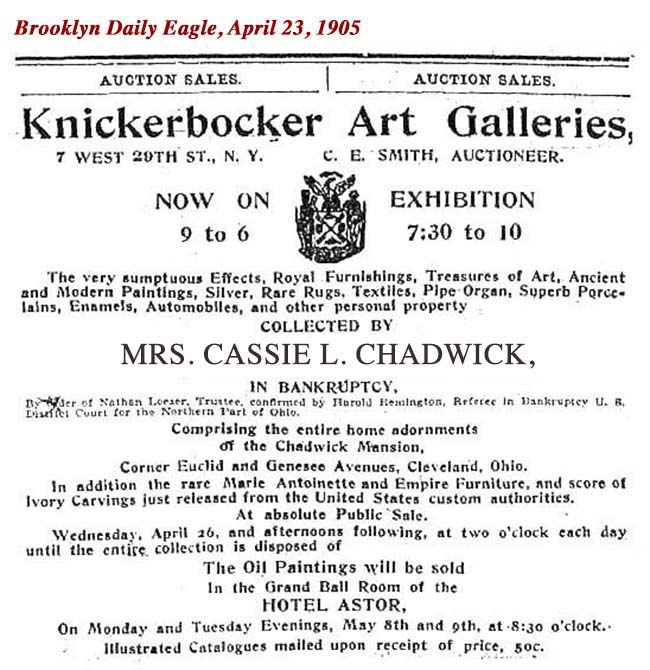

No vaudeville offer would ever come Cassie Chadwick's way, but a performance offer of another kind actually was received by Dr. Leroy S. Chadwick. It was made after an auction at what used to be his home.

|

New Haven Journal Courier, March 18, 1905

CLEVELAND, March 17 — The household property of Mrs. Cassie L. Chadwick was sold a auction today to A. G. Nelson of New York for $25,200. Samuel L. Winternitz of Chicago was the second highest bidder at $25,100. There were twenty bidders.

Clothing to the value of between $4,000 and $5,000 which Mrs. Chadwick held to be exempt from the claims of her creditors, under the bankruptcy laws, was no offered for sale today.

It was learned after the sale that Mr. Nelson bought the Chadwick articles for an art gallery in New York City. The twenty bidders were required to put up a guarantee fund of $1,000 each before they were permitted to bid, which was returned to all who made no purchases.

|

|

Send in the clown

The auction was held by the Savings Deposit Bank of Elyria, whose officials were wise enough to attach the right strings to the loans they had given Cassie Chadwick. The bank held a mortgage to the house on Euclid Avenue and title to all the furnishings, and the auction helped the bank recover a nice chunk of the money Mrs. Chadwick owed. As for A. G. Nelson, a week later it became clear why he had purchased Mrs. Chadwick's things: |

New York Telegraph, March 25, 1905

CLEVELAND, March 24 — While Mrs. Cassie L. Chadwick is languishing in jail, her husband, Dr. Leroy S. Chadwick will provide the musical features which have been arrange to accompany the public exhibition of the furnishings and trappings of the former Euclid Avenue residence of the fallen queen of finance.

To make the exhibition more attractive, C. E. Smith, representing Abram G. Nelson, the purchaser of the Chadwick effects, yesterday completed arrangements with Dr. Chadwick to have him give two organ recitals on the $9,000 organ which is one of the distinct features of the lavish furnishings of Mrs. Chadwick’s former home.

For $100 a week, Dr. Chadwick has agreed to give recitals from 11 a.m. to noon and from 4 to 5 p.m. daily. He will start upon his contract at once.

After the limited engagement of the attraction in this city, the Chadwick effects will be shipped to New York City to be placed on exhibition in the Knickerbocker art galleries. Dr. Chadwick will also go to New York to perform upon the organ. The promoters of the exhibition believe that daily performances by the husband of Mrs. Chadwick will go a long way toward swelling the receipts.

Dr. Chadwick last night admitted he had agreed to give two organ recitals daily. “The situation is just this,” said Dr. Chadwick. “Mr. Nelson want to sell the organ. He asked me to exhibit its fine points, and I agreed to do so.”

Mrs. Chadwick displays little interest in the fact her former possessions are to be exhibited. When informed that her husband is to play the organ, her only comment was: “The whole thing is ridiculous; it’s silly.”

|

|

| Dr. Chadwick soon came around to his wife's way of thinking and decided he wouldn't be part of the exhibit which opened at what formerly was his house, but was now referred to as "once belonging to Cassie Chadwick." One newspaper had this to say about the exhibition: |

New York Telegraph, March 27, 1905

The first performance was well attended ... The house has been only slightly re-arranged for the exhibition, but looks more completely furnished than before. The onyx stand that formerly supported the celebrated “perpetual” clock in the library has been replaced with a rug-covered table.

The house remains largely as Mrs. Chadwick left it, and most of the much-advertised features may still be found there. The big wax doll that was formerly laid out on a pillow on the library desk has been removed, however. The art experts in charge decided it looked too much like a dead baby.

In the library hangs the best picture Mrs. Chadwick possessed. It is a genuine Verboeckhoven bull, and is appraised at $1,500. On the same wall hangs a landscape dear at $5, and nearby is a copy of a Russian painting (subject, robbery of a mail coach), that is said to be a hot favorite for the distinction of being the worst picture in the house.

The owners do not expect to sell any of the property here, except possibly the organ. This, being mechanical, will be played during the exhibition by the manager, who is a musician himself. He regrets, however, that Dr. Chadwick will not be able to render some of his favorite pipe organ and also alto horn single-handed duets. The organ may not be moved to New York with the other stuff. The lot will eventually be put up at auction at New York.

|

|

|

Here a theory, there a theory

While Cassie Chadwick awaited trial, the press filled space by passed along various theories.

One held that Mrs. Chadwick selected Andrew Carnegie as her "father" on the chance the man would die before her scam was discovered. (Carnegie was 69 years old at the time of her arrest.)

If he were dead, she figured to have a shot at being awarded all that money — more than $16,000,000 — that was included in the phony estate she'd created from forged signatures. And while Carnegie claimed his signature was much different than those that appeared on Mrs. Chadwick's documents, experts who examined them said they were similar enough. |

|

A story in the Chicago Sunday Tribune (February 19, 1905) suggested Mr. Chadwick had hidden $1,000,000 in cash and $150,000 worth of jewels, and had hoped to sneak out of New York and sail to Europe where she would meet her husband in Brussels, where they would live happily ever after, with her son and his daughter.

Before sailing, the newspaper claimed, Mrs. Chadwick hoped to secure one more loan, for $500,000, but it fell through. When she left Cleveland for New York in late November, she hadn't anticipated being constantly watched by agents of the United States Secret Service.

The newspaper also said several of the women's creditors were upset when United States Attorney John J. Sullivan had the woman arrested when he did. The thinking, according to the Tribune, was that if she had been given more time, she would have led authorities to the money. As it was, her stash — if it did exist — was never found. Which killed the theory it was on deposit, along with her jewels, in a Brussels bank.

Some believed much of her money was tied up in property she had purchased in Vienna, Geneva, Venice, Berlin, Frankfort and London.

Some stories I found said Dr. Chadwick had filed for divorce before his last trip to Europe in November, 1904, but there's no record of him having done so, though other stories say he and his wife had been on the outs for most of their marriage and had been living apart for years, even during those few occasions they were under the same roof. When it came to being weird, Cassie Chadwick had nothing on the man she married, not once, but twice, both wedding eventually declared invalid. But, as mentioned earlier, in Ohio, where neither wedding ceremony took place, Cassie Hoover had become Dr. Leroy Chadwick's common law wife.

Weirdest theory was the one circulating in the hometown of Charles T. Beckwith:

|

Albany Argus, December 15, 1905

Oberlin, Ohio, is famous as the seat of a theological college; also, as the original of Mark Twain's "Hadleyburgh," the town which was virtuous because never tempted, until a cunning appeal to cupidity corrupted the whole town; also as the location of one of the bank's most largely victimized by Cassie Chadwick.

Whether there is any connection between these three propositions, or ideas, or not, there is a distinct connection between the Cassie Chadwick exploits and the sensation which now convulses Oberlin.

President Beckwith,, of the Oberlin bank, was ruined financially and undermined in health and spirit by the revelations of his connection with Mrs. Chadwick's transactions. He died before the government could try his case. Or at least, so it was said, but now it is asserted and widely believe in Oberlin that President Beckwith i alive in Canada. An Oberlin dispatch says:

"Beckwith is supposed to have died last March, and the question on everyone's lips tonight is: Was his body actually lowered into the grave last March, or was it a rough box filled with stones that was covered up by Mother Earth? This possibility of the aged banker being alive recalls with extraordinary vividness the circumstances surrounding his death. It was in the dead of night that the report was sent out from the Beckwith home that the aged banker had died. No one but members of the family was permitted to see him.

"Tonight's report says that an undertaker was not engaged to embalm the body, although an Oberlin undertaker late tonight asserted that he had been called in after death. The funeral was private and newspaper men who called were denied admittance to the home. Utmost secrecy was maintained throughout. Dr. Bruce, the family physician, when seen tonight, said he was not present when Beckwith died, but declares that he attended the funeral and saw Beckwith's body in the coffin. It is expect that not only the authorities, but the insurance companies will make an investigation."

|

|

| The first thing wrong with that dispatch from Oberlin is Beckwith died in early February, not March. |

When in doubt, faint

From the time she realized arrest was imminent, and more so while she lived in the Cuyahoga County jail as her trial approached, Cassie Chadwick became afflicted what women long ago called "the vapors." Iri Reynolds took things a step further. |

Minneapolis Journal, February 15, 1905

New York Sun Special Service

CLEVELAND, February 15 — Mrs. Cassie L. Chadwick is giving her jailers and attorneys anxiety because of frequent fainting spells. On one occasion medical assistance was necessary to revive her. Her counsel says Mrs. Chadwick has a severe case of heart failure and may collapse and die before the time for her trial arrives.

Iri Reynolds, the man who Mrs Chadwick made trustee of her magical $5,000,000 in securities, has been confined to his bed for several days with grip. The worry due to his connection with the Chadwick affairs has weakened him, and in his delirious moments he talks of nothing else. His family and physicians are greatly alarmed.

|

|

While there may have been a serious, but undetected root cause to Mrs. Chadwick's condition, Iri Reynolds recovered and lived until 1928, when he died at the age of 83.

On March 11, the Chadwick trial concluded when the jury found her guilty on seven of the 16 counts in her indictment. She was sentenced to ten years in the Ohio Penitentiary, but it would be almost ten months before all of her appeals were exhausted. Until then she remained in the Cuyahoga County jail. Her case eventually reached the United States Supreme Court, but the justices either rejected her appeal or refused to waste their time on it, and in January, 1906, she finally checked in to the Ohio Penitentiary in Columbus.

Weeks earlier, federal authorities sought permission to confine her to a federal prison, either in Atlanta, Georgia, or Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. This was done out of fear the state of Ohio might pardon her. However, Judge Taylor, in the United States district court, ruled she should serve her time in Columbus, and federal authorities would just have to trust the Ohio board of pardons to do what was right.

Her 10-year sentence officially began January 12, 1906, but with good behavior she could be out in less than seven years. However, for awhile it appeared she might serve all her time in the penitentiary hospital, where she was confined almost as soon as she arrived. After four days, she was put the work with a needle, making buttonholes in shirts, from her hospital bed. Prison officials said she would continue at that work until she was well enough to run a sewing machine. |

Couldn't have enough jewelry

In addition to her trial, Cassie Chadwick also testified in March during a hearing in bankruptcy court where efforts were made to recovered whatever money she had in order to pay her creditors as much as possible. Not surprisingly, she claimed she did not owe as much as her creditors claimed, nor did she receive as much money as people believed.

Rather than borrowing between $1,000,000 and $2,000,000, she said, "I do not owe much more than $750,000," sounding as though that were a paltry amount.

Some of those who'd loaned her smaller amounts had been given pieces of her jewelry as security. Mrs. Chadwick mentioned receiving a loan of $17,000 from Ludwig Nisson of New York, and says she secured it with a string of pearls he later sold for $60,000.

Jewelry was her weakness, and she purchased it everywhere she went. She bought so much jewelry in Europe that, for awhile, government agents believed she might be a smuggler. A lot of her jewelry was still in Brussels, held hostage by a firm that claimed she owed them thousands of dollars.

The impression I received from stories I read is her smaller creditors were given jewelry as security and may have profited from their dealings with Mrs. Chadwick. However, the bigger loans — those made by the bank in Oberlin and its unfortunate president, Charles T. Beckwith, and Newton and Friend — were not repaid, and there were some who felt these people had gotten a taste of their own medicine.

That's why, in December, 1904, about the time Cassie Chadwick was arrested, she received some unexpected emotional support: |

New York Sun, December 12, 1904

BOSTON, December 11 — Mrs. Hetty Green, who stopped over in Boston last night, probably the last person in the world who would be expected to defend Mrs. Cassie Chadwick, placed herself on record as a friend of that woman, for the time at least.

“I don’t know the woman; I never knew her kind; but you just wait until the thing’s over and you probably won’t find her to be quite as wicked as she's painted,” said Mrs. Green. “Probably when they get through with it, they will find some of these big bankers and lawyers have been behind her, using her to get money. It would not surprise me a bit to find they and not she have got the money.

“Now perhaps you don’t think that is possible, but I’ve had a lot of experience and I know more about bankers and banks than most people. All the crooked ones ain’t in jail yet, and the Lord knows there’s enough of them there. And you can’t believe all the District Attorneys say about her, either."

|

|

| Hetty Green, 70 years old at the time, was known as the richest woman in America, and our biggest miser. Word was she wore the same dress every day until it was in tatters. Only then would she buy another one. Because she was female, her nickname was “The Witch of Wall Street." Were she a man, she would have been called a wizard. Everyone seemed to agree she was shrewd, but honest. She was born in New Bedford, Massachusetts, to a family which owned a large whaling fleet. She began with a modest fortune, and doubled it several times. |

Threatened by her own lawyer

Mrs. Chadwick's testimony during bankruptcy court obviously was self-serving, but probably contained grains of truth. Certainly the widow of W. C. Jutte, a Pittsburgh coal operator, believed Mrs. Chadwick were believable enough to help her in a lawsuit she was filed against James W. Friend and his business partner, Frank N. Hoffstot. Mrs. Jutte felt the two men had taken advantage of her husband's unstable mental condition to steal everything Mr. Jutte had owned before he committed suicide in Atlantic City in 1905. Jutte had attempted suicide four years before that, but survived a bullet to his head. The second time he shot himself in the chest.

Anyway, when Mrs. Jutte instituted her lawsuit in 1906, her lawyers wanted to take a deposition from Mrs. Chadwick at the Ohio Penitentiary. This led to yet another stranger-than-fiction incident in the life of the mind-reading con woman.

Francis J. Wing, a former United States district judge, was one of Mrs. Chadwick's lawyers before she went to prison. In September, 1906, he admitted threatening her with dire consequences if she went ahead with the deposition for Mrs. Jutte. He told Mrs. Chadwick the deposition would hurt her chances of ever being paroled from the Ohio Penitentiary because it would make an enemy of Mr. Friend, who had friends powerful enough to have her parole applications denied.

She resented the threat and went ahead of the deposition, which became a big issue in Mrs. Jutte's case, especially when it was sealed for several months. When it was finally entered into the case, weeks after Mrs. Chadwick had died in prison. the judge shrugged, and expressed surprise anyone felt there was significance to her deposition. He ruled in favor of Friend and Hoffstot, saying Jutte was of sound mind when he took out a loan from the two men, a loan he couldn't repay, thus costing him his entire estate.

Apparently, what Mrs. Jutte and her lawyers thought there was importance to Mrs. Chadwick's testimony that Friend had referred to Jutte as insane and in no condition to handle his own affairs.

Also in the deposition, Mrs. Chadwick went into detail about six loans she had received from Friend, and the total amount loaned was $798,200, not the $225,000 she claimed during the 1905 bankruptcy proceedings. |

Loans or blackmail?

To me, the biggest mysteries about the woman originally known as Elizabeth Bigley, are how she operated in Toledo as clairvoyant Lydia Devere, and the period between her release from prison in 1893 and her marriage to Dr. Chadwick, when she called herself Cassie L. Hoover.

A story in the New York Sun (December 9, 1904) estimated that by the year of that marriage, she had borrowed $300,000, again on no credit, from some prominent men who, perhaps wanting to avoid embarrassment, chose to forget the loans and deny any knowledge of the woman.

There seems to be evidence she entered her marriage to Dr. Chadwick with more money than he had — maybe much more. A story in the Chicago Sunday Tribune (December 4, 1904) says she owned a house on Lake Avenue, on Cleveland's west side, where she reportedly was living in style. What remains unknown to me is whether this Lake Avenue residence was that brothel where she and Dr. Chadwick supposedly met. In any event, in 1897, the woman was in debt to no one, maybe because those "prominent men" didn't loan the woman money, but paid her for services rendered, or as blackmail.

Despite those who have belittled the woman's looks, I think men found her attractive, at least until the last few years when she seemed to age rapidly. The photo of her at the top of this page — one that was taken in prison — is positively scary. She was only 49 years old, but looked like she was in her 60s. Like Charles T. Beckwith, she may have willed herself to die. She popped up in the news several times while at the penitentiary, mostly because of her health problems, real or imagined.

|

Milford (MI) Times, September 28, 1907

A suspicious and shrewd prison doctor caught Cassie Chadwick, serving a term in the Ohio penitentiary, in her attempt to secure sympathy and release by feigning illness and faking blindness. So she will be put to work again.

The records of Mrs. Chadwick’s alleged confinement as Madame Devere many years ago show that she succeeded in getting a parole on the ground of ill health. At that time she fooled the medical staff by well-shammed sickness. It was this history that caused the suspicion she was trying the same old dodge, and the plan of the physician proved its correctness.

Next week Mrs. Chadwick will be back at her task of sewing for the rest of the inmates of the big prison.

|

|

| But two weeks later she was dead, passing away on her 50th birthday. One of her sisters arranged for her body to be taken home to Canada for burial. |

| |

| The con lives on |

| |

|

|