| HOME |

|

|

Adversity met its match in Oel Johnson Johnson was born in Alexander City, Ala., son of William Otis and Boba Dilla Townsend Johnson and twin brother of William Otis Johnson Jr. Oel was one of 11 children – eight boys and three girls – raised on a farm in the Fish Pond Community of Coosa County, Ala., not far from Alexander City. He was a 1934 graduate of Auburn University – then known as Alabama Polytechnic Institute – earning bachelor of science and masters degrees in chemical engineering. “My childhood was not unlike many other of that day,” he said in a 1986 interview with Island Events, a Hilton Head publication. “I grew up in the fields and in the woods, learning to do the things that youngsters on any farm learned to do. My family did have a deep respect for education, however, and our father helped my two older brothers borrow the money to go off to Auburn. As it turned out, we were all encouraged to go to college and the older brothers helped where they could. When all was said and done, seven of the eight Johnson boys graduated from Auburn.” Johnson was an officer in the Civilian Conservation Corps, an early employee of the Tennessee Valley Authority and, finally, in 1938, went to work for Coca Cola. His first assignment was to go to Mexico to set up a series of bottling plants. In September 1940 he became the chemist in the Far East Division stationed in Manila, The Philippines. When the Japanese attacked The Philippines in 1941, Johnson, an Army Reservist with ROTC training, was called to active duty as a first lieutenant. He was a field artillery officer on the Bataan Peninsula when he was captured by the Japanese on April 2, 1942. “I was single and spent a lot of time exercising,” Johnson said in the 1986 interview. “I think I stood the march well because of being in such good condition. “The distance wasn’t that far, really. I marched 77 kilometers – about 50 miles. The thing that made it so devastating and the reason so many died was that the general level of health had been lowered by the condition and lack of proper diet prior to the surrender. Many of the people who failed to survive were already seriously ill when it began. And there were constant snap searches by the Japanese. Almost anything they found could be called contraband and the punishment was immediate execution.” After seven months in Philippines, he was one of 1,500 prisoners jammed into the hole of a freighter. Many prisoners died during 26-day voyage to Japan. Those who survived were held in camps near Osaka until the Japanese surrendered in August 1945. “There was a job in prison camp that nobody wanted,” Johnson said. “That was acting as go-between for our group of 500 prisoners. It involved spending time in the Japanese office every day, being involved with every controversy, every beating of a prisoner. I chose to take on this duty because I felt it would be better for my health, and I’m glad I did. It was a great experience for me even though the job carried no immunity. I was beaten myself on numerous occasions. “It was not a popular job, but it did give me a chance to learn more about their language. The phonetic writing in Japanese has only 72 characters, unlike the more formal ideographic languages. I learned certain verbs and nouns that I judged would be useful. “When our men had to go out and work in factories or on other jobs, they would sometimes come in contact with Koreans and other virtual slave laborers who had access to newspapers. They would then smuggle them back into camp and give them to me to translate. That was dangerous, however, as the Japanese were brutal over such offenses and searches were common. Most of the time I simply slipped newspapers out of the office where I worked. The results, however, were much the same. We were able to keep up with the war.” Johnson, who had suffered bouts of malaria and dysentery, finally was liberated on September 10, 1945.

By then he was again working for Coca-Cola which had presented Johnson with a check for the entire time he had been a prisoner. His first post-war assignment for Coca Cola was to set up plants in Panama, Colombia, Venezuela and Brazil where his daughter Olinda was born in 1947. In 1950 he was transferred to New York where for the next 22 years he was in charge of the manufacture of Coca Cola syrup in the various countries of the world that were part of Coca Cola Export. They made the syrup, but the ingredients of the secret formula had to be shipped under strict security precautions. Part of Johnson’s job was to make sure those precautions were adequate. The family lived for 22 years in Irvington on Hudson, N.Y., where a son, Jeffrey, was born in 1951 and a daughter, Elizabeth, in 1960. Johnson was made a vice president of Coca-Cola Export in 1963. He retired in 1972 and moved to Hilton Head Island where he was a member of Sea Pines Club and the Presbyterian Church. He enjoyed playing and watching golf and was an avid fan of Auburn University sports, particularly football. During his 1986 interview with Island Events he said he earned his master of science degree, in part, because “my brother (Otis) and I got a break during our junior year at Auburn. Neither of us was heavy enough for football, and when Auburn announced it had decided to start a polo team we went out for it. We were on the first team that Auburn ever had. We played in ‘32 and ‘33 and then because I had another year of eligibility I went back for the fall of ‘34. I was able to get an assistantship in the chemistry department.” He continued to play polo after college, in Mexico and in The Philippines at the Manila Polo Club. He was survived by his wife, Dorothy Donnan Johnson; daughters Olinda Johnson Major of Bluffton, S.C., and Elizabeth Johnson of Atlanta, Ga.; one grandchild, Meridith Johnson Major of Warwick, R.I.; his younger brothers John W. Johnson of Goshen, Ind., and James A. Johnson of St. Paul, Minn., and sisters Mary Johnson Adams of Alexander City, Ala., and Boba Dilla Johnson Courtney of Opelika, Ala. (His two sisters would die within two years; his widow, Dorothy, died in August 2006.) “Looking back on it,” Johnson said in 1986, “I see that I learned a major lesson from my imprisonment which probably has stood me in good stead ever since. I learned not to make a foolish request. If you asked for something ridiculous, the Japanese not only did not grant it, they generally beat you for being so foolish. Later, in business, although the penalties weren’t so severe, I remembered the lesson and never made a request that I didn’t consider reasonable.” |

| HOME | CONTACT |

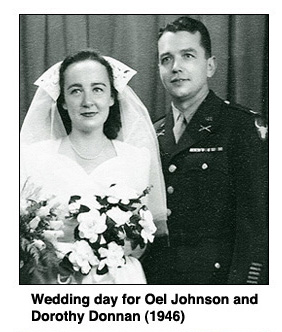

It was during his three-month recovery in an Army hospital at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, that he met Dorothy Donnan of York, N.Y., then an Army nurse. They were married on May 26, 1946.

It was during his three-month recovery in an Army hospital at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, that he met Dorothy Donnan of York, N.Y., then an Army nurse. They were married on May 26, 1946.