| HOME |

|

|

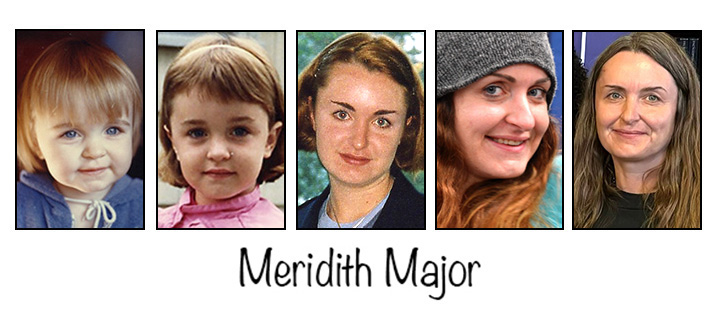

The old rules didn't apply Linda and I had been lulled into complacency by my son, Jeff, and my daughter, Laura, who were usually compliant, seldom rebellious and only occasionally troublesome, despite having to adjust to their parents' divorce. At first, it was a typical divorce, lots of bickering and lawyering. My ex-wife, Karla, and I had joint custody of the children, and within a year our lives began a slow, but steady transformation from soap opera to a sitcom in which we were all part of one happy family that happened to live in two houses about five miles apart. Three years after we were married, Linda and I decided it was time to have a child of our own. And on August 4, 1980, Linda gave birth to Meridith, who would very quickly teach us we didn't know diddly about parenting. Everything we thought we'd learned with Jeff and Laura went out the window. None of the old tricks worked with Meridith. INITIALLY we weren't concerned. After all, it was common for newborns to have odd sleeping habits, to awaken several times during the night, depriving their parents of a good night's rest. We figured it was a phase Meridith would soon outgrow. Not so. Meridith arrived in this world as a night person. Thirty years later she still stays up until the wee small hours. However, when she was four years old, Linda and I sought professional help. We'd been putting Meridith to bed between 8 and 9 p.m., but like a boomerang she'd return to wherever Linda and I were. In my frustration I suggested we tie the kid to her bed. It was a joke, obviously, but what happened next was just as outrageous, thanks to a psychologist who knew less about child-rearing than we did. We sensed this immediately, but decided to give the man two chances to prove us wrong. For us this was a sort of Mythbusters experiment. We completely disregarded one piece of advice, which was, in effect, to offer bribes, which would have had us playing tooth fairy every night for a kid who wasn't losing any teeth. This psychologist was pleased as punch that money motivated his son. Not only was this a terrible idea on the face of it, but Linda and I knew that Meridith, even at age four, would insist on negotiating the amount of money being offered. At this point in her life Meridith had the makings of a sports agent. The doctor's second suggestion seemed even more outlandish, but since this was professional advice, sort of, and since Linda and I didn't want to prolong the nonsense, we said, what the hell, this could be interesting – as long as we didn't take it too far. Of all the parental concerns I've ever had, this turned out to be the most laughable. The idea was to put a latch on the outside of Meridith's bedroom door. We were told to put her to bed, then, in effect, lock her in her room and engage in a war of wills, ignoring her cries until she yielded and crawled into her bed for the night. So in the interest of science, we tried it. We ushered her into her room, issued our ultimatum, and left, latching the door behind us. The yelling began immediately, but subsided within thirty seconds. That's how long it look Meridith to rip open her door, pulling loose the latch. The psychologist's little trick had turned our daughter into The Incredible Hulk. We were so proud. Which is why we were often tempted to resort to the age-old remedy that had fallen out of favor in the 1980s. Yet parents continue to fall into the trap of making the threat. And so it was with us: "Young lady, you're going to get a spanking!" Our young lady had learned to talk by quoting TV dialogue and music lyrics. Her response to this threat was to stick out her butt and snarl, "Hit me with your best shot!" I WAS NEVER ONE to encourage mimicry in my children. Visitors didn't have to worry that I'd summon my toddlers into the living room for a boob tube recital. ("Okay, Jeff, say, 'I can't believe I ate the whole thing!' " "Okay, Laura, say, 'That'sa one-a spicy meatballa!' " "C'mon, Meridith, say, 'Awesome, baby!!' ") However, Meridith's use of clever, albeit impudent comebacks and pop song hooks was very effective, at least, on me. Instead of fanning my anger, her insubordination often made me laugh. Just when I should have been sternly reprimanding her, I'm thinking, "How did she come up with that one? Damn, she's good!" Linda, on the other hand, was not amused, correctly reasoning Meridith would exploit my weakness, which she did. Over and over. Unlike a sitcom parent who forms a bond with a child by ... what's the phrase ... understanding where she was coming from, I merely became Meridith's stooge. ("Oh, yeah, Mom freaked out, but you know Dad ... he laughs at anything.") Whether it began as a ploy to postpone bedtime, I don't know, but soon after Meridith entered elementary school she expressed interest in staying up with me to watch college basketball games, especially those involving Syracuse and Duke. She became a huge SU fan for awhile, particularly during the Lawrence Moten-Mike Hopkins era. The two of us would go to the Providence Civic Center (before it became the Dunkin' Donuts Center) to risk evil looks from Friar fans while we cheered for the Orange. One of my fondest memories of Jeff and Laura as pre-schoolers was telling them stories, usually around bedtime. It was something my father used to do with me, and he'd improvise tales, often built around my favorite Walt Disney character, Donald Duck. Jeff and Laura preferred Batman and Robin stories. I thought my Gotham City tales were quite clever; at least, that's what Jeff and Laura led me to believe. So I approached storytelling time with Meridith full of confidence. That big bang you might have heard 34 years ago was my confidence being shattered. Five words into my first bedtime story, Meridith interrupted with, "That's not how it goes." I reminded her it was MY story. "I don't care," she said. "That's not how it goes." There were exceptions, crazy exceptions, almost all of them involving tales the two of us concocted from one special book. Not a story book, but rather an old Betty Crocker children's cookbook that Linda had had since childhood. For some reason Meridith enjoyed my nonsense about the fruits and vegetables pictured in the book, particularly one Eddy the Eggplant, a character more prominent in Meridith's childhood than Little Red Riding Hood, Goldilocks, Bambi, Pinocchio. The Three Little Pigs, Bert, Ernie, Kermit and Cookie Monster combined. The key: the Betty Crocker book was about food and how to prepare it. There was a bit of Martha Stewart in our little Meridith. A tiny bit, perhaps, but you couldn't fail to notice it. AS YOUNGSTERS, Jeff and Laura often were noncommittal. Probably it's fairer to say they had a desire to please. When informed we were going out to eat, they'd offer no opinion about the restaurant, being flexible enough to accept whatever one we mentioned. On the other hand, Meridith demanded a say in choosing the restaurant. She did this soon after she started talking. "Daddy" wasn't among her first 20 vocabulary words. It got bumped to make room for "Lobster!" Linda and I pitied the first guy who took Meridith out to dinner. For that I blame Linda's parents, the late Oel and Dorothy Johnson, whose visits from South Carolina always included dinner at the Harborside Restaurant in East Greenwich, RI. My in-laws loved lobster and the Harborside was their favorite lobster restaurant. Meridith was still a toddler when she discovered blue cheese dressing at a terrific little Italian restaurant called Olerio's (which, sadly, changed hands and no longer exists). Luckily the whole family liked Olerio's because when Meridith was in one of her blue cheese-dressing moods she'd make us miserable if we suggested another restaurant. Saying 'No' to Meridith could be painful, as I discovered one night after dinner. She wasn't yet four and was going through a stretch we referred to as "The Terrifying Threes". She hadn't finished her meal – didn't even come close – and was told she couldn't have dessert. Linda and I adjourned to the living room to read the newspaper. I heard Meridith stomping around in the kitchen and told her again that she wasn't getting dessert. Suddenly it was quiet. Too quiet, as they used to say in movies. Then WHACK! Something hit me on the top of my head. Twice. It was one of Meridith's dolls, luckily a soft one, that she was holding by one leg and using as a bludgeon. It was right out of 'The Bad Seed', but even Linda coudn't help but laugh. Took me a few seconds, but so did I, though not enough to benefit Meridith. There was no dessert and from then on Meridith found better ways to play with the doll. MERIDITH WAS born with a wonderful sense of direction. Not that it was always wonderful to have her as a passenger. Other kids would ask, "When are we going to get there?" Meridith would complain, "You're going the wrong way." This was probably something she got from my mother. Not the sense of direction, but the need to play navigator. Both Meridith and my mother believed that to get from Point A to Point B there was only one way. Their way. However rigid she may be about directions and story plots, Meridith negotiates other aspects of her life like a comic at the Improv. I mentioned there's a bit of Martha Stewart in her – must be their shared Polish heritage – and it shows in Meridith's creative approach to decorating and cooking. She likes to cook and is quite good at it, which is amazing because she couldn't follow a recipe if her life depended on it. She prefers to make do with what's available, which is why in the kitchen she's not so much chef as mad scientist. But with delicious results, most of the time. Every mad scientist goes awry occasionally. ALL THREE CHILDREN like to fish. None of us is particularly good at it, since the Major fishing tradition was handed down from my father, who did all of his during two-week vacations at Sandy Pond, NY. All he was after was sunfish, a small, lightly regarded pan fish. Oh, I'm sure he would have enjoyed catching something larger once in awhile, but he was fishing for food, and, to him, no fish tasted better than sunfish. Until Meridith came along, we continued to do almost all of our fishing at Sandy Pond, even though we were living in Rhode Island where it seemed everyone had a boat and was out on Narragansett Bay or the Atlantic Ocean. They were certainly catching bigger things than sunfish. Meridith didn't push us that far, but she did want to participate in something Jeff and I had tried a few times – without success. There's one Saturday each year when several hundred Rhode Islanders go freshwater fishing. That's the opening day of trout fishing season in April when the hordes descend on streams and ponds that have been well stocked with farm-bred trout, most of which are caught before the sun goes down. And so, at Meridith's insistence, we gave it a try – and netted our first trout. Notice I said "netted", because we actually didn't catch the trout; someone else had and kept it long enough for the fish to die before releasing it back into the stream. Meridith saw it and picked it up with our net. This made her more determined to land one on her own. Meridith's nagging interest in fishing prompted me to explore other opportunities, which is why we wound up sampling more than a dozen freshwater places all over Rhode Island. All three children benefited – and all three turned out to be better at fishing than their father. We never did catch any trout, but we all had pretty good luck with largemouth bass. Meridith started to believe she could catch fish anywhere, refusing to accept my reasons to avoid certain waters, such as the Pawtuxet River as it flows past the Warwick Mall where Linda briefly had a part-time job. The river reportedly was so polluted in that location that no fish could possibly survive. Meridith stubbornly believed otherwise, so I took her there one afternoon to prove she was wrong. Within seconds she had the last laugh, catching a good-sized bluegill that looked none the worse for having been bred in toxic waste. (We took the fish home and put it in the huge puddle atop the cover of our above-ground swimming pool. We were pleasantly surprised that evening to notice the bluegill didn't glow in the dark. When winter arrived a few weeks later, we returned to fish to the river.) A few years later, during a visit to Linda's parents in Hilton Head, Meridith wanted to fish the lagoon next to the condominium where we were staying. We had brought along a pole, but hadn't yet found a place to buy bait. No problem, said Meridith. Roll some bread into tiny balls. Sure, Mer. Again, it took only seconds for Meridith to get a hit from something in the lagoon. She set the hook, and reeled toward shore. It was a bass, one of the larger ones we'd ever seen at the end of one of our poles. Our excitement was short-lived, thanks to a set of eyes we noticed about ten feet behind the fish – and closing. It was an alligator. Meridith put down the pole and we retreated several yards to let nature take its course. Even Meridith wasn't about to challenge a gator. MERIDITH SHARED her sister Laura's love of horses and began riding lessons when she was in second grade. Both girls took to riding quickly and would eventually compete in shows, riding horses owned by their instructor, Cynthia Bowen. Laura retired from the horse show circuit before Meridith started. The horses the two of them rode never would have guessed the girls were sisters. I know little about riding, having been on a horse only once in my life, for a newspaper assignment in Syracuse. Neverthess, when we attended horse shows I could predict the rider who'd win the blue ribbon in Laura's events — she was named Donna Szablinski. Fortunately for Meridith, years later, none of her competitors was named Szablinski. So my analysis of my daughters' riding styles is rooted in ignorance where dressage is concerned and based almost entirely on my own experience with them. Laura, I thought, handled stubborn horses with patience, attempting to bend the horse to her will through friendly persuasion. She was our horse whisperer. Persuasion was almost always necessary during one event in which horses were required to walk a wooden platform. Whether it was the surface or the resulting noise, this task caused many horses to balk or circumvent the platform. Meridith? Well, I'll never forget the look on her face at one Connecticut show when her horse, whose show name was Tiffany's Witch, hesitated at the base of the platform. I was reminded of Alex Karras in 'Blazing Saddles.' But no punch was thrown. Meridith remained in the saddle and very strongly urged the horse forward, Witch quickly realizing it was in her best interest to cross the platform. Meridith, you see, was the horse intimidator. Afterward I congratulated Meridith. Once again she had had her way with one of God's creatures. Then I gently patted the horse and sighed, "Witch, I know exactly how you feel." |

| HOME | CONTACT |