| HOME |

|

|

|

|

|

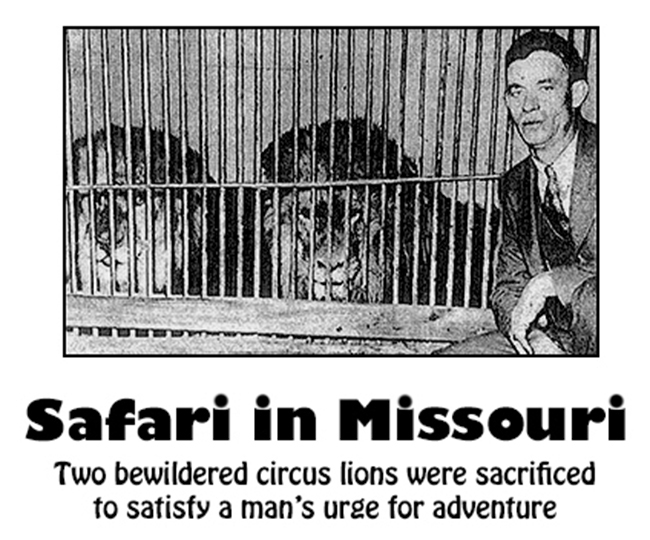

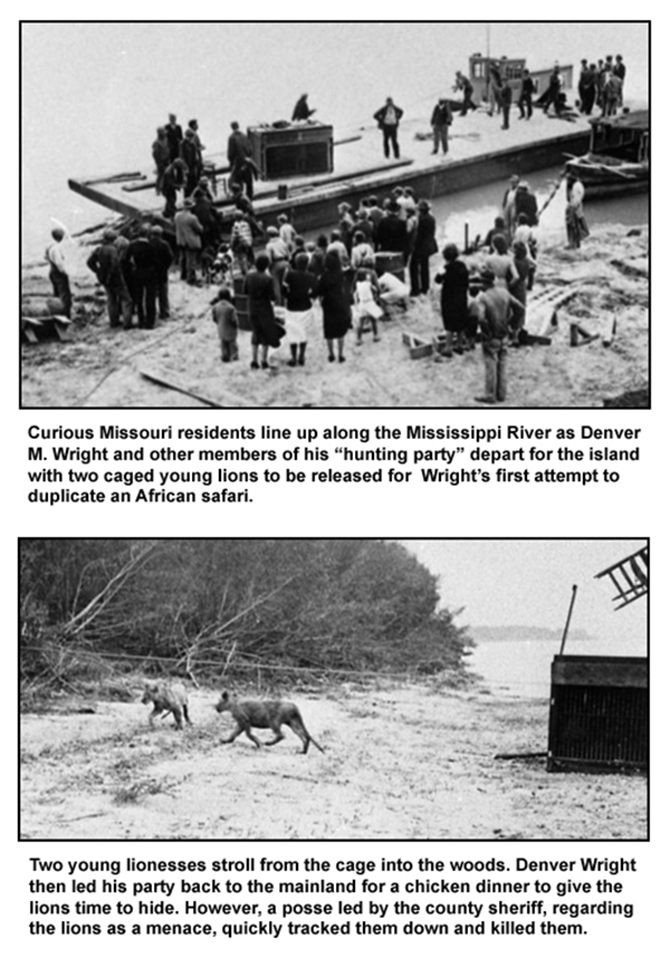

By JACK MAJOR His wife didn't want him to do it. The ASPCA tried to dissuade him. Area sheriffs spoke out against the idea. But Denver M. Wright, a St. Louis leather manufacturer, went ahead with his ill-conceived plan for what he termed an African-style safari. Not once, but twice. Though woke idiots do it all the time, it's unfair and ignorant to impose today's sensitivities on the attitudes and behavior of people who lived more than 80 years ago. During the 1930s, Ernest Hemingway was considered a man's man, and hunting big game was, for many, the ultimate manly sport. However, what Denver M. Wright did was, even at the time, considered cruel, pathetic and ridiculous. But apparently he broke no laws. His first Missouri safari took place in October, 1932. Why and how he'd acquired two ten-month-old female lions was never made quite clear by Wright, who altered his answer each time he was asked. The story is a failing circus sold the two lions to Wright, who kept them for a while in his backyard in Brentwood, a St. Louis suburb. His idea was to sell tickets to men who wanted to participate in a lion hunt somewhere in southeast Missouri. Wright's uncertainty about where he'd release his lions was worrisome to people in that part of the state. Wright then announced he'd hold the safari on an island in the Mississippi River, near the small town of Commerce, Missouri. The sheriff of nearby Mississippi County complained he'd recently had to hunt an escaped circus lion, and didn't want to go through that again. Stories about this "safari," and the one staged three months later, are confusing when it comes to location and the lawmen who spoke out against them. Some claimed the island actually was in Kentucky; the second safari may have strayed into Arkansas. Also at issue is the age of this first pair of lions. A story written by Sam Blackwell for the Southeast Missourian not only sets the age at 10-months, which makes this a pair of juvenile lions, but also says they had names — Nellie and Bess. Which makes what happens next even more pitiful. Feeling the heat, Wright told an Associated Press reporter he had offered the lions to the city of Cape Girardeau, but the city refused to take them. The mayor of Springfield asked for them, but Wright shrugged him off and began heading toward the island, attracting many curious onlookers in the process. |

|

|

|

|

|

Sheriff Hotchkiss wasn't being completely honest. For one thing, the lions actually were killed by a man named Tom Wise, who accompanied the sheriff to the island, along with two newspaper reporters. According to "The Great Commerce Lion Hunt," a story on the Sporting Classisc Daily website, the sheriff's visit was intended to determine the actual danger presented by the lions. However, Wise said one of the lions dashed toward him, so he opened fire. Maybe, but after reading several stories about this fiasco, and the even greater one to come, I tend to believe it was the intention of Sheriff Hotchkiss (spelled Hodgkiss in the online story) to put an end to the safari in a way that Wright couldn't arrange to re-schedule it. Which is why Nellie and Bess had to be killed. Wright and some who wrote about this event referred to the the sheriff's party as "interlopers," which wasn't true. If anything, the sheriff had more right to visit the island than did Wright's group. The bodies of the two dead lions were given to Wright who had them stuffed and mounted for a place in his game den. And while Wright had made it seem as though the two young lions originally had been forced upon him, he went out and purchased two more from a circus. This time they were full-grown males (see photo at the top of the page). Another "safari" soon was underway, with Wright determined to make sure no "interlopers" would be able to interfere. A motion picture photographer would accompany Wright' party to take pictures of the hunt, and Wright said he'd donate his profits from the picture to charity. |

|

"Southeast Missouri's Strangest Hunt," a story by Allison Vaughn from March 11, 2007, might well be accurate, but several details do not agree with 1933 newspaper accounts. Unfortunately, Ms. Vaughn's story has disappeared from the internet. According to that story, Denver Wright set out to gather 18 hunters and about twenty "husky Negroes" to act as "beaters" on his safari, which he planned for Hog Island, somewhere in the Mississippi River. Newspaper stories at the time made it appear only a small group participated in the second hunt, and the "beaters" were either rather-be hunters or curious people who paid for the privilege. Reports about this sad affair were all datelined Wolf Island, Missouri, which is not an actual island, but a tiny community southeast of Cape Girardeau, a mile or so from the Mississippi River. Apparently there is an island by that name nearby, but an Associated Press story on January 20, said that particular island was part of Kentucky, and C. R. Faulkner, sheriff of Hickman County in that state, said he would not permit the lion hunt to be held there. Stories say Wright set up camp on Hog Island, but I've yet to find such a place in that part of Missouri. Where Wright actually took his two lions and how many men accompanied him is uncertain. Why anyone would tag along was puzzling because one of the conditions of the hunt was that Wright or his son would do the killing. Only one thing is sure: folks who participated had a dreadful experience. It was, after all, the middle of winter, albeit in the southern half of the country. The weather did not cooperate. Neither did the lethargic lions, who had to be chased away from Wright's camp after they were released from their cages. Finally, the animals wound up behind a barbed wire fence that separated them from the hunters and their tents. However, the lions eventually became more active, destroyed a part of the fence, indicating they could have gone after the men if they wanted, but chose to stay on their side of the fence. Nonetheless, several of Wright's "big game hunters" spent a sleepless night. Wright decided to go ahead with his hunt, despite the weather and the reluctance of the doomed lions to go along with what seemed a very sick joke. It's hard to imagine anyone getting pleasure from a hunt in which the prey is practically shouting, "Shoot! Just get done with it!" The Associated Press reported what happened the next day: |

|

|

|

In 1935, Wright went into Mexico and killed deer, wild hogs and an ocelot. The next year he went after panthers and alligators in the Florida Everglades. The last mention I found of him was from 1953 when the Eastman Kodak Company refused to deliver a movie Wright made of a South American tribe because its members did not wear clothes. Kodak was afraid of violating state and federal laws relating to obscenity. Finally, a U. S. District Court judge in Chicago ruled the film should be turned over to the Bible Institute of Los Angeles, as Wright had intended. He said the film would be used to teach medical missionaries. The lawsuit had dragged on for two years. According to "Southeast Missouri's Strangest Hunt," Wright wrote a book about killing his lions. Apparently it was written in the third person, and he sometimes referred to himself as "the courageous Wright." That's not an adjective I would have chosen. |

|

| HOME | CONTACT |