|

Syracuse Journal, January 12, 1921

ATHENS – The American “dollar princess,” formerly Mrs. William B. Leeds, may become queen of Albania. It was reported here today that Albanian leaders have urged her to accept the throne. Rumors here said the princess had ordered a magnificent coronation robe in New York – a regal garment embroidered with Byzantine eagles. |

|

| |

|

By JACK MAJOR

"The Dollar Princess" was a popular musical that opened in London and New York in 1909. The title later was used to describe a woman who went from a stenographer in Ohio to real-life princess in Greece. What made it possible was the fortune left to her by her wealthy second husband, William B. Leeds. I knew nothing about her or the musical until I stumbled upon the above item and my curiosity took over.

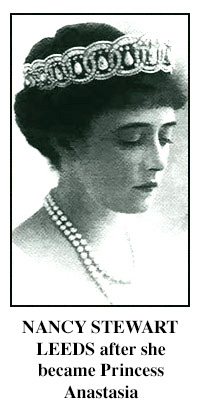

Princess Anastasia was her royal name. And while she did not become queen of Albania, it's possible an offer was made. Reportedly Lithuania had offered a package deal to her husband, Prince Christopher of Greece, saying he and his wife could rule as king and queen, but he declined. That anyone even considered the possibility was because the American princess had in abundance what the Greek royal family lacked – money.

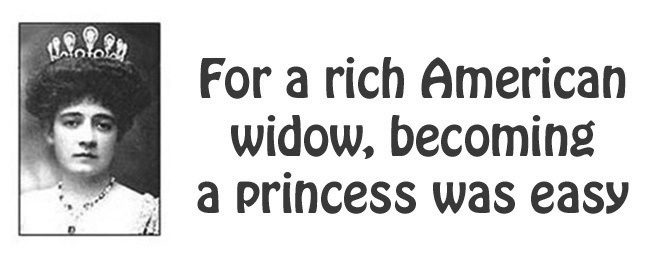

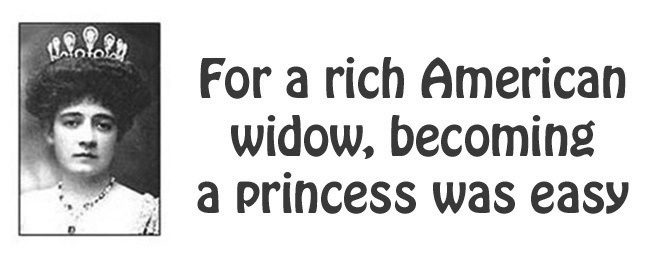

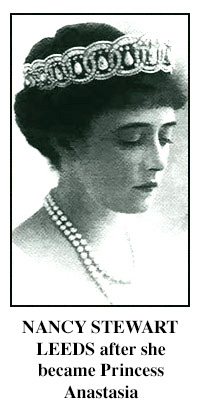

In 1921, this rich American woman-turned-princess was very popular throughout Europe. Hers is a fascinating story, one made possible by her beauty and, I suspect, a fierce determination to be wealthy, a goal reached in 1900 with her second marriage. She was only 22. At that point she seems to have set a third goal – to be accepted in high society.

She was born Nonnie May Stewart in Zanesville, Ohio, in 1878, but her family moved to Cleveland where she was better known as Nancy Stewart. (Her childhood friends called her "Pinkie," which doesn't fit the image she would make for herself as an adult). As a teenager, she entered a brief marriage with banker George H. Worthington, who died in 1898 shortly after their divorce.

As a stenographer, she attracted the attention of William Bateman Leeds, who'd made millions of dollars in the tin-plating business. He divorced his wife in 1900 and a few days later married Nancy Stewart Worthington. Forever after some would refer to her as Nancy Leeds or Mrs. William Leeds, though her husband died in 1908. The woman's claim to the title of princess – and a new nickname – wouldn't be established until 1920 when she married Prince Christopher of Greece and Denmark, brother of King Constantine I of Greece.

THE WIDOW Leeds and Prince Christopher became engaged in 1914, but the marriage was delayed for six years, supposedly by his family's opposition to the match. I suspect that is only partly true. The Greek royal family might have resisted because, according to their marriage laws, Mrs. Leeds would herself become royalty.

However, the Greek royal family was in deep financial trouble, which made the American a great catch for Prince Christopher. It may have been Mrs. Leeds who delayed the wedding until after World War I. The Greek royal family was connected to the German royal family and was sympathetic to the German cause. Mrs. Leeds might have been playing politics, realizing she'd be scorned at home if regarded as a supporter of an enemy of America.

But she finally married Prince Christopher and in the process became Princess Anastasia. For the next few years there would be stories that she used her money to put her brother-in-law, Constantine, back on the throne of Greece. These stories seemed more believable than her denials. However, no amount of American money could resolve the problems facing Greece, which was at war with Turkey in 1921, a situation that made life uneasy for Prince Christopher's family.

Even after her marriage, the American press often referred to her as "The Tin Plate Heiress," though the nickname "The Dollar Princess" became more popular. One variation was "The Million Dollar Princess."

THAT THE Greek royal family was related by marriage to the Romanovs, the Russian royal family unseated by the Bolshevik Revolution, created a sometimes confusing, eventually frustrating situation for the Leeds family. Nancy Leeds became Princess Anastasia, but obviously wasn't the mysterious Romanov grand duchess, Anastasia, subject of much controversy in the 1920s and '30s, and later a 1954 Broadway play, the 1956 Ingrid Bergman movie, an animated 1997 film, and several television documentaries. But Nancy Leeds' marriage to Prince Christopher, who was born in Russia, established a family connection between the two women.

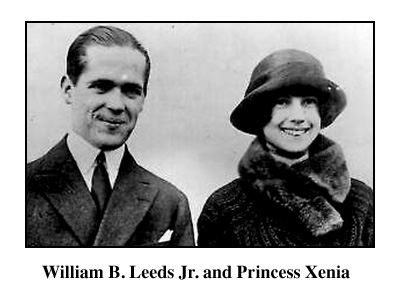

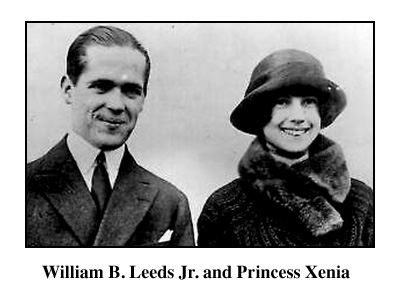

That connection became stronger in 1921 when the only child of the American heiress-turned-Greek princess, William Bateman Leeds Jr., married a Russian princess, Xenia, who was living in Greece. Later, when Leeds and Princess Xenia were living in Long Island, they paid the way to America for a woman who claimed to be the Russian Anastasia. The woman, known then as Anna Tschaikovsky, later as Anna Anderson, had a history of mental illness and was dismissed as an impostor. She lived in relative obscurity until 1927 when a newspaper article about her attracted the attention of Princess Xenia, who knew the real Anastasia, but had last seen her in 1913.

Anna Tschaikovsky lived for awhile at the 54-acre Leeds estate in Oyster Bay, Long Island, and Princess Xenia was one of the few members of Russian royalty who believed the woman's story. For awhile it looked as though the visitor would hang around permanently, but she did not get along with Xenia's husband. It was William B. Leeds Jr. who sent Anna Tschaikovsky packing. It wasn't long afterward that the Leeds marriage ended. Anna Tschaikovsky (Anderson) kept in touch with Princess Xenia, who continued to believe the woman was the real Anastasia, even after almost everyone else conceded it had been proven otherwise.

BUT I'M GETTING ahead of myself. Her son's marriage to Princess Xenia seemed to go against Princess Anastasia's wishes. At the beginning of 1921, she told reporters:

“I love America and still consider myself an American, despite the relinquishment of my citizenship. I want William to return to the United States and become a useful citizen of his native land. And I hope he marries an American girl.”

Unfortunately, Princess Anastasia was ill ... so ill that weeks later she underwent surgery and her son was summoned to her side, which wasn't easily accomplished because the teenager was thousands of miles away. His visit would prove to be one of those good news/bad news things. His presence cheered his mother, but hours later she went into an emotional decline because William B. Leeds Jr. abruptly proposed marriage to a 17-year-old princess. And she had said yes.

Later she tried to postpone the wedding, saying her son and his intended bride were too young for marriage. She claimed that upon learning her son had proposed to the princess she cried for three days and refused to see him. However, the marriage took place a few months later.

PRINCESS ANASTASIA was dying, but the public was led to believe her illness, while serious, was not fatal. There were references to an intestinal problem, with denials of the cancer that would take her life on August 29, 1923. She spent much of that time in Paris and London and also made a valiant visit to the United States. Her son and his wife spent most of the next two years at her side.

Before leaving England for America, Prince Christopher said that after the funeral he would return to Europe with William B. Leeds Jr. and Princess Xenia. He also declared all three of them would live in Europe permanently. However, the prince spoke only for himself. Three months later, Leeds and his wife announced they were leaving Europe to live in the United States.

Princess Anastasia's will – indeed, almost everything I've read about the estate of William B. Leeds – is beyond my understanding when it comes to who got what, when and how. Estimates about the size of the estate vary wildly, as do guesses about how much money Princess Anastasia and her son had at various times in their life. The usual estimate is that William B. Leeds Sr. was worth at least $30 million dollars when he died.

The princess also had a collection of gems, gifts from Leeds and European royalty, including jewels valued at hundreds of thousands of dollars. These were distributed among her husband, son and daughter-in-law.

One thing is very clear: There was more than enough money for everyone – the princess, Prince Christopher, William Leeds Jr., Princess Xenia, and various royal relatives who came begging. (The 1920s were a bad time for royalty, especially those too lazy to work.) Also, the former Nonnie Stewart took good care of her sister, Margaret Stewart Green, and her family. |

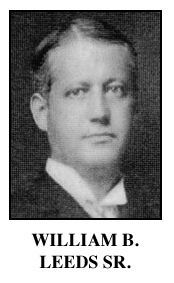

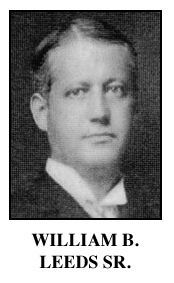

IT'S TIME FOR a few words about the man who made all this possible.

William Bateman Leeds Sr. died in 1908. What follows may be true, mostly true, or partly true, but undoubtedly incomplete.

How he became a multi-millionaire known as "the tin plate king" involves several things I don't fully understand ... things such as tariffs, trust-building and watered-down stocks. My information, such as it is, came from various websites, several of which obviously copied items word-for-word from other sites  and passed them off as their own. (There's a lot of litter along the information highway. The most annoying may be those websites that promise to be your source for all there is to know about almost every person who ever lived, but deliver only a squib they lifted from Wikipedia ... plus a lot of advertising.) and passed them off as their own. (There's a lot of litter along the information highway. The most annoying may be those websites that promise to be your source for all there is to know about almost every person who ever lived, but deliver only a squib they lifted from Wikipedia ... plus a lot of advertising.)

I found most of my information on an unusual website, www.fultonhistory.com, which offers about a zillion pages from old newspapers. It doesn't have every newspaper, nor every year from the newspapers that are available. But there's enough available to keep you busy for the rest of your life. The site seems to be used mostly by people on the same mission that led me to it in the first place – to discover and read about my ancestors. Some of mine made the news in 1921, which is how I accidentally stumbled across Princess Anastasia and Leeds.

Newspaper articles – which form the backbone of this project – aren't exactly reliable, particularly those from the glory days of the industry when each large city had several newspapers. Competition induces speed, and deadline-beating reporting often leads to mistakes compounded when an inaccurate story becomes the basis for a follow-up. This may be especially true in the case of stories about the Leeds family, especially when royalty entered the picture, because the combination of money and arrogance created a strong barrier against intrusion by the press.

Because I did this online, I couldn't help but consider how much easier it is today to tap sources of information – yes, even bad information – than it was when these articles were written. Reporters almost invariably identified William B. Leeds as "the tin plate king" without explaining why he had the nickname or, for that matter, explaining what they meant by "tin plate." Many years later, Leeds' two children would be identified as "tin plate heirs" or "sons of the tin plate king." By the 1920s people would be hard-pressed to identify "the tin plate king," and finding the answer might take some time. Ah, the difficulties of living B.G. (before Google). The answer to the "tin plate king" question, of course, is ...

WILLIAM B. LEEDS. His wasn't exactly a rags-to-riches story because he seems to have started out in Richmond, Indiana, as an ambitious, middle-class fellow who probably would have led a comfortable life even without the breaks that came his way. He doesn't seem to have been particularly likable – few narrowly focused opportunists are – but at least in the beginning he often stopped to smell the roses. And that's because his first business was operating a nursery which specialized in the sale of roses, shrubbery and greenhouse plants.

But that was a brief period in his life. At 22, his direction changed. The year was 1883, and whether it was his roses, his personality, his good head for business or the fact he had chosen the right woman to marry, Leeds made a favorable impression on Henry Miller, a relative of his fiancée and a superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad. In 1883 Leeds found a new career when Miller secured him a position with the railroad's engineering corps for the territory west of Pittsburgh. It wasn't a cushy job, but it did offer advancement.

A month after starting his new job, Leeds insured his future – he married Jeanette Irene Gaar, also of Richmond. I have no idea whether this was true love or good planning on Leeds' part – certainly the love didn't last – but I'll assume that for the first seven years of their marriage they were an average young couple, hard workers with big aspirations, perhaps benefiting only a bit from her family's wealth.

Then came 1890. Her father died she inherited a substantial amount of money. How much money is unknown, but in 1890 you could do a lot with, say, $100,000, especially if you were friends with a banker who wasn't afraid to wheel and deal.

Leeds convinced his wife to let him use all or a big chunk of her money to buy a nearby tin-plating plant. And then he turned to his best friend, who just happened to be a wheeling-dealing banker.

For what happened next, I turn to "A History of the United States Steel Industry," by Herbert Newton Casson (1859-1951), who had this to say in a section labeled "The Napoleons of Tin Plate." |

| |

There were four in the Moore or Rock Island group—all dashing knights of the dollar—whose adventures would read like the voyages of Sindbad the Sailor. They were D. G. Reid, W. B. Leeds, and the Moore brothers. [Chicago lawyers,William Henry Moore and James Hobart Moore.]

As for Reid and Leeds, they had been Damon and Pythias since childhood. Both were born in Richmond, Indiana, then a farming town of five or six thousand inhabitants. Dan Reid lived on a farm, Billy Leeds in the town. Dan began his business career by sweeping out a bank, working up, after a while, to be its president. Billy began as a rodman on the Pennsylvania Railroad, and climbed to the position of branch superintendent.

As soon as the thirty-dollar-a-ton duty was placed on tin plate, in 1891, the two young men swooped down upon the feeble little tin-making plants that had been fighting bankruptcy for twenty years, and swept them all together into a Tin Plate Trust before they had time to find out what was happening.

Tin plate was one of the youngest branches of the steel trade. There was a small plant at Leechburg as far back as 1872; but it was impossible to compete with Wales and make a fair profit. No tariff was levied on tin, because its importers were influential in politics, and because it was generally supposed that the making of it was a Welsh secret.

Reid and Leeds resolved to make the experiment on a large scale. The day after the McKinley tariff bill was signed, they ordered tin-making machinery — a quarter of a million dollars' worth — from Wales. A body of Welshmen came with the machinery; but at first they failed to make Reid and Leeds successful.

Then came the Presidential campaign of 1892. Tin plate was a national issue. Workmen paraded in Pittsburgh, wearing tin caps. Democrats claimed that campaign money was being used to start tin-plate works. The whole industry was thrown into the political cauldron. But the two young Indianians never weakened. They adapted their machinery to American raw material; they set inventors to work; and in the end they remade the industry on American lines.

Within six years they had combined two hundred and seventy-eight mills into a fifty-million-dollar corporation. Reid and Leeds paid enormous prices for independent plants; but they took long views of the tin-plate business, and came out worth probably forty millions apiece [when they sold their business to what was about to become the U. S. Steel Company]. They and the Moores received from J. P. Morgan $140,000,000 in U. S. Steel stock when the big corporation was formed. They at once bought control of the Rock Island Railroad.

|

|

| |

THE U.S. STEEL deal was made in 1901, but Leeds was already a fairly wealthy man by then. But as his financial struggle ended, so did his first marriage. In 1900, he divorced the woman whose money made his success possible. And she agreed – for $1,000,000, which at the time was considered the largest sum of money ever paid to obtain a divorce. In view of what would happen a year later, it might seem that even with $1,000,000, the woman was short-changed. However, I think it's safe to say Jeannette Irene Gaar Leeds did not regret her decision. She used the money from the divorce settlement to buy the Richmond, Indiana, newspaper, and gave it to her son, Rudolph G. Leeds, who ran the Richmond Palladium for 50 years. (Reportedly, Rudolph received a million dollars after his father died.)

As for Rudolph' father, he'd picked out a second wife even before his divorce. She was a 22-year-old stenographer, Nonnie May Stewart Worthington, who had shed her first husband two years earlier. Mrs. Worthington, better known to friends as Nancy Stewart, grew up in Cleveland. Where she was working in 1900, I don't know. One story said Leeds noticed her in an office, but didn't say if she was one of his employees or a stenographer elsewhere.

In any event, it would have been impossible not to notice her – wherever she was. One story called her "the most beautiful girl in Cleveland," which  may not seem all that impressive, but from two newspaper photos that must have been taken when she was in her early 20s, I'd say the word "stunning" didn't do her justice. (The photo on the left was taken years later, but the date is unknown.) may not seem all that impressive, but from two newspaper photos that must have been taken when she was in her early 20s, I'd say the word "stunning" didn't do her justice. (The photo on the left was taken years later, but the date is unknown.)

Leeds was smitten and would remain so for the rest of his life, which, tragically, would come in 1908. He and Mrs. Worthington were married at the home of her parents in Cleveland. Leeds reportedly gave his new bride gifts worth at least $500,000.

The couple settled for awhile in Chicago. A year later, thanks to J. P. Morgan and U.S. Steel, Leeds was richer by many millions of dollars. After he and his partners invested their profits in the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad Company, Leeds became president of the company.

In 1902 Leeds purchased a 263-foot, $500,000 steam yacht, Noma. It was one of the fastest and most spectacular yachts of its day. I mention this because it might help explain the interest – obsession is more like it – that would become so noticeable in his son, William Jr., who someday would have a similar yacht, called Moana. (I haven't found a reason for either name, though, in the case of Moana, the world means "ocean" in most Polynesian languages, and Leeds Jr. spent a lot of time there.)

At the end of 1903 Leeds and his friend and partner D. G. Reid reportedly had a falling out. Leeds resigned as president of the railroad, but was made director of several other companies.

AFTER THAT he and his wife were little seen in the Midwest because they preferred New York City, with summers in Newport, Rhode Island, and frequent trips to Paris.

In 1905, Leeds, only 44 years old at the time, suffered a stroke, which left him partially paralyzed. The next year he suffered a second stroke.

After three summers in Newport, leasing the cottage called "Rough Point" (many years later the home of Doris Duke), the Leeds decided to buy the property from Frederick W. Vanderbilt. (Her poor reception in Newport reportedly made Mrs. Leeds bitter and was the reason she spent so much time in Europe after she became a widow.)

Leeds suffered a third stroke in 1907, then died several months later, on June 23, 1908, at the Hotel Ritz in Paris.

HE WAS BURIED at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, New York City. in a mausoleum designed by John Russell Pope (who also designed the Jefferson Memorial). Pope was also engaged by Mr. Leeds at the time of his death, and was in the process of designing a new residence for the Leeds on Fifth Avenue.

William Bateman Leeds had a brother, Warner Miflin Leeds, who also became a millionaire in the tin-plate business. I find it odd that most stories about "the tin plate king" and his partners make no mention of Warner M. Leeds, but he definitely played a significant role. (The one story that did give him credit went so far as to put him on equal footing with his brother.)

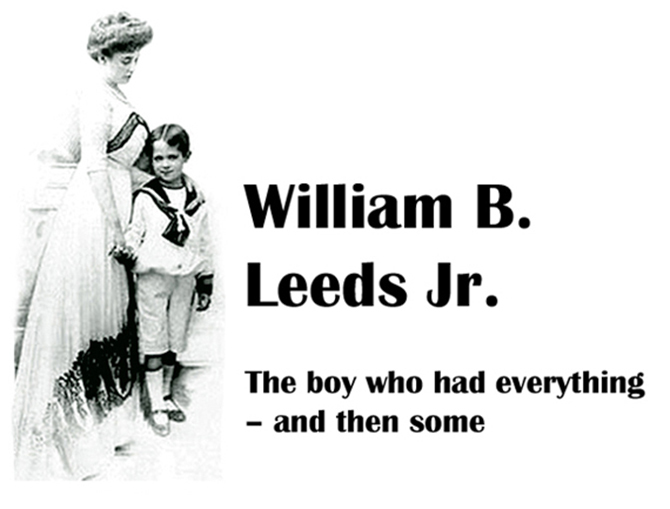

And now we move on to the man whose life was shaped by his father's money and his mother's marriage to a prince: |

|

For the first nineteen years of his life, William Bateman Leeds Jr., could have been called "The Boy in the Bubble." There was nothing seriously wrong with him, as things turned out, but his mother seemed to think he was unusually frail. So she coddled the boy, often from long distance through nannies and nurses.

Since her son had inherited a lot of money from his father, the princess made sure her boy was well protected against kidnappers, even when she was on another continent, as she often was while he was educated in the United States. Later she felt he would be better off in Europe.

And so, in 1911, when Mrs. Leeds went to London for an extended visit, she set this agenda for her son, then nine years old:

“I think I shall educate William in England. You see, he is fortunately or unfortunately wealthy in his own right. He will grow up to be ‘rich’ and I do not think that the sons of American millionaires are a particular credit to society because in their idleness they become dissipated. They do not work and most of them drink.

“Hostesses here often have to apologize for the condition of their young men guests, whereas in England no man would ever appear twice in an intoxicated state. Of course, the young men in the social life of England do not work, but they go in for sports and are healthy, strong and normal – and they do not drink as much as the idle young men of America.”

Exactly where William B. Leeds went to school from 1911 through 1920, I don't know. For a period he was enrolled in a private school in New Jersey where his mother had leased or purchased an estate. Whether he moved to England and began school there soon after her 1911 interview, I do not know. He must have spent several of his formative years there, however, because by adulthood he apparently spoke with a British accent.

ASTHMA MAY have been at the heart of the frequent stories about the boy's frail condition. But in 1915, when he accompanied his mother on a visit to Switzerland, he apparently seemed like a normal, healthy and active 13-year-old. He certainly would become an active adult ... almost hyperactive, given his almost non-stop travels.

By 1921, Leeds Jr. was out of his bubble, becoming a certified globe-trotter. He was in Sumatra when he learned that his mother was seriously ill. He had an unexpected, but temporary health problem of his own – a badly infected insect bite on one of his arms – but he headed for Greece, completing the last leg of his journey, from London to Athens, by airplane. In those days flying was still a bit of a novelty; dangerous, too. His mother urged him to come by boat, but he paid no heed.

After a stop in New York to visit an eminent surgeon about the insect bite infection, he resumed his trip, and three weeks later he arrived in Athens, his arm healed and his mother relieved that he had had a safe trip. His presence momentarily revived her spirits and seemed to improve her health. But she suffered a setback when he again overruled his mother and proposed to Princess Xenia.

HIS MOTHER must have known such a marriage was likely. Months earlier there was speculation her son would be matched with Princess Olga, granddaughter of King George I of Greece. She would go on to marry Prince Paul of Yugoslavia in 1923. One of their daughters, Elizabeth, was the mother of actress Catherine Oxenberg.

If the Greek royal family did pull the strings, they were in for a disappointment. Within a couple of years they'd be forced into exile, broke and sponging off royal relatives in other European countries. Leeds would offer some support, but most of his family's money that wound up in Greek pockets was put there by what his mother's will provided for Prince Christopher.

After some delay, teenagers William B. Leeds Jr. and Princess Xenia were married. The weddings (there were three of them) were held not in Athens, but in Paris, where Anastasia had a second operation for the cancer that would take her life.

Except for a brief separation in late 1922 when Princess Anastasia and her husband, Prince Christopher, went to the United States, and Leeds and his wife had to remain awhile in Paris, these four pretty much lived together until Anastasia's death.

WILLIAM B. LEEDS JR. and Princess Xenia were an active couple who were part of the social scene wherever they were, but just as often they went in different directions and spent much of their married life in different time zones. Through it all they were able to maintain a high degree of privacy. One senses they were friends, not lovers, and by 1929 their marriage had become mutually inconvenient.

On February 24, 1925, the couple had their only child, a daughter named Nancy Helen Marie Leeds. (Among the many newspaper items I found there was no mention of Leeds and his daughter ever doing anything together. Perhaps William B. Leeds wasn't cut out to be a father.)

My reading of Princess Xenia, in view of her life in America, is she had her own agenda, and it concerned her Russian roots and her Romanov relatives, not the Greek royal family her grandmother, Grand Duchess Olga Constantinova, had married into in 1867. Princess Xenia might not have survived until 1921 if her mother, Princess Maria of Greece and Denmark, had felt the same way about her heritage.

Princess Maria's mother, Grand Duchess Olga, was Russian, but her father was King George I of Greece. After she married Grand Duke George Mikhailovitch of Russia, Princess Maria had to leave Greece, a land she loved. She did not adjust well to living in Russia and became increasingly unhappy in her marriage. In 1914 she took her two daughters, Nina and Xenia, and left for England, telling her husband it was because of the girls' health (which must have been a popular excuse in those days).

The outbreak of World War I prevented her from returning to Russia, something Princess Maria might have anticipated. Duke George Mikhailovitch never again saw his wife or his daughters. He was a general during the war; afterward, when the Russian Revolution broke out , he was imprisoned by the Bolsheviks, then shot by a firing squad in 1919.

These were turbulent times. Confusing, too. In a way, World War I continued well into the 1920s as European nations were in conflict over which country was entitled to huge chunks of territories that had gone back and forth for centuries. Revolution was in the air, not only in Russia, and in Greece the royal family was losing its grip on the throne.

WHEN THE DUST settled, Princess Xenia decided living in the United States was her best option. There Russian exiles lived freely, though not often well. Her situation, of course, would be different. Eventually, however, she'd manage to alienate most of her relatives who had managed to escape Russia. |

|

What finally may have sunk the marriage was the belated interest Princess Xenia took in the woman who in the early 1920s claimed to be Grand Duchess Anastasia of Russia's royal family, the Romanovs. Xenia and the real Anastasia were cousins. It was in 1928 that Xenia became aware of the woman, so she and her husband invited Anna Tschaikovsky (later Anna Anderson) to stay at their estate in Oyster Bay, Long Island. Princess Xenia was one of the few Russians – of those who had ever met Anastasia before the Bolshevik Revolution – who believed Anna Tschaikovsky was the real deal.

Real deal or not (it's 99.99 per cent certain the woman was an impostor), William Leeds found her presence increasingly annoying, finally ordering her to leave. Anna Tschaikovsky might really have been a Polish peasant, but she had a royal temper.

In her book, "A Romanov Fantasy: Life at the Court of Anna Anderson," Frances Welch said this about the would-be Anastasia who lived for awhile with Leeds and his wife. |

|

"Years later Anna gave characteristically sparse descriptions of the appearance of her host and hostess; she appeared to recall further, with disapproval, her host’s colorful misdemeanors. ‘The estate was Oyster Bay at the ocean where I was living. Xenia Leeds, nicely tall, well groomed, and ... William Leeds, a tiny creature – like a little dwarf with brown eyes." |

|

| All the drama finally got to Leeds. But even after the would-be Anastasia departed from Oyster Bay, the drama continued, and the long anticipated divorce of Leeds and Princess Xenia finally happened in 1930. |

| On water, Leeds seemed jinxed |

Near as I can tell, Billy Leeds, as he was known, seldom had a job. In 1930 he was president of something called Air Services, Inc. I have no idea whether this was a charter or delivery company, or something else, like perhaps his personal air taxi service. I found a newspaper story (Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 15, 1930) about Leeds being in Havana, phoning his company at Roosevelt Field, Long Island, and instructing his pilot, Frank Cordova, to pick him up in Cuba in his Lockheed-Sirius low-wing monoplane.

In March 1931, Leeds signed on as mooring master of the submarine Nautilus, which Sir Hubert Wilkins planned to take on an under-the-ice Polar expedition that summer. "Definite decision as to whether he will make the voyage depends on Leeds’ physical condition," reported the Albany Evening News (March 27, 1931). "He is reported a sufferer from bronchitis. He would be in complete charge of the craft at intervals when it is moored."

Leeds was friends with Sir Hubert Wilkins from their around-the-world flight aboard the Graf Zeppelin in 1929. They also were passengers on another flight two years later. Among the things Leeds packed for those trips was a portable gramophone. No word on his record collection ... or whether he went on the Polar expedition.

Obviously, he loved to travel, usually in one of the many yachts and large vessels he would own over the years. He also was interested in air travel, getting a pilot's license and buying airplanes, one of them named after his wife Princess Xenia. That plane, flown by another pilot, was entered in a transatlantic race in 1927. None of the competing planes finished the race.

Leeds' love of the sea resulted in several adventures, some of the life-threatening. He had so many boat-related narrow escapes that some folks considered him a jinx at least on the water.

On March 30, 1924, Leeds and Princess Xenia had a narrow escape from drowning when the launch in which they were traveling sank while traveling from Brunswick, Georgia, to Saint Simons Island.

On September 4, 1924, while staying at their summer home on St. Regis Lake in the Adirondacks, Leeds saved Princess Xenia from their speedboat, Wildcat, which caught fire when a bystander tossed a match into oil-coated water. Flames enveloped the boat in which Mrs. Leeds was sitting. Her husband got into the boat and beat off the flames with a coat.

In 1927, Princess Xenia piloted a new torpedo speedboat over Long Island Sound on November 21 at what then was  considered an astounding 63.07 miles per hour. The boat was equipped with a 500-horsepower Wright Whirlwind airplane motor. It had a streamlined body thirty-eight feet long. considered an astounding 63.07 miles per hour. The boat was equipped with a 500-horsepower Wright Whirlwind airplane motor. It had a streamlined body thirty-eight feet long.

Prince Eric of Denmark, Prince Christopher, the son of the late King George of Greece, and naval attaches of foreign embassies and legations in Washington were among the twenty-four passengers on the craft as Mrs. Leeds guided it to a new unofficial record for a craft loaded to 2,500 pounds. Leeds sat beside his wife during the test.

The name of that boat was "Fan Tail," and it became another chapter in the story of the Leeds jinx. Eight months after Princess Xenia's sprint over Long Island Sound, the boat exploded, nearly killing Leeds and a guest, Adele Astaire was severely burned.

Ms. Astaire and her brother and dancing partner, Fred Astaire, were weekend guests at the Leeds’ Long Island home at Cove Neck. She and Leeds had just entered the boat to take a trial spin. He started the motor. The backfire ignited gasoline seepage in the hull of the craft. The boat almost immediately was enveloped In flames.

Leeds picked up Miss Astaire, who had collapsed, and lifted her to the landing stage. Then climbing out himself he pushed the Fan Tail out into clear water. An explosion occurred a moment later and the boat was destroyed.

DISASTER WAS averted, thanks to the quick reflexes of Leeds, who must have been wondering how long his luck would last. But he pushed it anyway, and in December 1929, purchased a steam yacht called the Winchester. Leeds had it overhauled and renamed it Flying Fox, claiming it would be the fastest steam yacht. The 165-foot yacht could accommodate 52 passengers, but had sleeping quarters for only eight.

On July 11, 1930, five months after his divorce, Leeds staged another heroic rescue at sea, this time saving a 24-year-old telephone operator, Olive Hamilton, whose rowboat overturned while she was trying to get a  close-up look at the big yacht anchored off an Atlantic City beach. Sparks would fly and a lifelong relationship was underway, though marriage was six years down the road. close-up look at the big yacht anchored off an Atlantic City beach. Sparks would fly and a lifelong relationship was underway, though marriage was six years down the road.

Perhaps Miss Hamilton deliberately tipped the boat, anticipating the result that eventually was achieved. She was an uncommonly attractive woman, apparently well-suited for the world of Billy Leeds, frequently mentioned in gossip columns.

Had his mother lived to see this rescue, I have a feeling she would have greeted the young woman with a knowing smile and this observation: "Nicely played."

Ms. Hamilton was often described as a telephone operator, but her job was at an Atlantic City hotel where she handled room service calls. She and Leeds were not strangers on the day of the rescue. They had met three years earlier, though they had no relationship until he pulled her from the water.

I found one story that said Ms. Hamilton moved to Manhattan, but did not explain how she supported herself in an East Side apartment. It's always risky to assume, but my guess is Leeds supported her until he was ready to get married again. |

* I repeated what was published in newspaper accounts of the rescue which described Olive Hamilton as a 24-year-old telephone operator. According to findagrave.com, the woman was born in 1894, which would have made her 36 years old at the time, eight years older than Leeds and 39 years older than her second husband, James Brick II.

|

LEEDS MADE headlines in late May, 1935, when he and two companions were reported missing aboard a 26-foot fishing launch en route from Miami to Bimini. President Franklin D. Roosevelt told the Navy and Coast Guard to begin a systematic search. Your tax dollars at work.

Once again luck was on Leeds' side. Rough seas kept him from reaching Bimini, so he turned around back toward Florida and arrived several hours later in Fort Lauderdale.

In 1936 Leeds and Olive Hamilton defied the curse. They were married aboard his palatial yacht Moana and honeymooned in the British West Indies. The first time Leeds was married, to Princess Xenia, there were three ceremonies. This time there were two because the first ceremony was performed at sea, and to insure the legality of their marriage, a second ceremony was performed in Miami.

Sure enough, the curse struck. On the voyage back to New York from Florida, Leeds was confined to his cabin aboard the Moana. The New York Post (June 18, 1936) said he suffered an attack of chronic appendicitis. Leeds had plans to attend that evening's fight between Joe Louis and Max Schmeling. This was their first fight, won by Schmeling in round 12. Whether Leeds got to watch, I don't know.

On November 20, 1936 several newspapers carried a story about the just-published 1937 Social Register. Apparently as punishment for marrying a former hotel employee, William B. Leeds was dropped from the register. Also missing, for the second year in a row, was heiress Barbara Hutton, who at the time was Countess Haugwitz-Reventlow.

A FEW MONTHS later Leeds announced he would make The Moana his full-time residence. His Long Island estate, called Kenwood would be auctioned off. He also announced intention of selling his 17-room Beekman place apartment. The yacht was more spacious than either land residence.

After the United States entered World War 2 the Leeds' yacht, Moana, had different duties. So did William B. Leeds. |

New York Post, December 24, 1942

Lyons Den by Leonard Lyons

Billy Leeds owned the Moana, one of the largest yachts afloat. He lived on that vessel for many years, sailing around the world. The Moana had a crew of 59, a swimming pool, a hospital – and Leeds was master of it all. The Moana now is owned by the U. S. Government. Three members of the crew are now lieutenant commanders in the U. S. Navy. And on Monday, at Norfolk, Billy Leeds will become a petty officer in the Coast Guard. |

|

In 1944 Leeds purchased a memorable anniversary present for his wife – the Nassak (aka Nassac) Diamond. Also called The Eye of the Idol, the diamond is 43.38 carats and had been acquired in 1940 by American jeweler Harry Winston. Mrs. Leeds wore it in a ring. The Nassak was considered one of the world’s great diamonds in the 1940s. (It was sold at auction in New York in 1970 to a Connecticut trucking company executive.)

In December 1945, Nancy Helen Marie Leeds, daughter of Leeds and Princess Xenia, married Army Lt. Judson Wynkoop Jr. of Syracuse.

On August 10, 1946 Princess Xenia married husband number two, New York lawyer Hermann Jud.

As for Leeds, he was about to make a surprising decision, one that raised a question about his financial condition. Leonard Lyons' column in the New York Post (November 4, 1947) said Leeds was going to sell his yacht. "The current Moana," said Lyons, "is a 117-foot ship, formerly Harold Vanderbilt's Vagrant." Leeds told Lyons he had no intention of buying another.

He dropped out of public view, purchased an estate in the Virgin Islands and on December 3, 1971 died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound. Friends said he had been seriously ill with cancer.

Princess Xenia had passed away on September 17, 1965. Her daughter, Nancy Leeds Wynkoop died in 2006.

Olive Hamilton Leeds re-married after Leeds' death. She and her husband, James Brick II, lived in the Virgin Islands and she died in 1988. |

| |

|

and passed them off as their own. (There's a lot of litter along the information highway. The most annoying may be those websites that promise to be your source for all there is to know about almost every person who ever lived, but deliver only a squib they lifted from Wikipedia ... plus a lot of advertising.)

and passed them off as their own. (There's a lot of litter along the information highway. The most annoying may be those websites that promise to be your source for all there is to know about almost every person who ever lived, but deliver only a squib they lifted from Wikipedia ... plus a lot of advertising.) may not seem all that impressive, but from two newspaper photos that must have been taken when she was in her early 20s, I'd say the word "stunning" didn't do her justice. (The photo on the left was taken years later, but the date is unknown.)

may not seem all that impressive, but from two newspaper photos that must have been taken when she was in her early 20s, I'd say the word "stunning" didn't do her justice. (The photo on the left was taken years later, but the date is unknown.)

considered an astounding 63.07 miles per hour. The boat was equipped with a 500-horsepower Wright Whirlwind airplane motor. It had a streamlined body thirty-eight feet long.

considered an astounding 63.07 miles per hour. The boat was equipped with a 500-horsepower Wright Whirlwind airplane motor. It had a streamlined body thirty-eight feet long. close-up look at the big yacht anchored off an Atlantic City beach. Sparks would fly and a lifelong relationship was underway, though marriage was six years down the road.

close-up look at the big yacht anchored off an Atlantic City beach. Sparks would fly and a lifelong relationship was underway, though marriage was six years down the road.