|

Part 1:

Until a few months ago, I didn't know who Cassie Chadwick was, let alone details of her criminal career, but it didn't take long to accumulate enough material for a five-part telling of her unbelievable story.

Cassie Chadwick was the name that identified the Cleveland con woman who was nationally infamous in 1904 when it became known that her claim of being the illegitimate daughter of wealthy industrialist Andrew Carnegie had fooled bankers for almost three years, enabling her to borrow perhaps $2 million or more with "securities" that were virtually worthless.

Lydia Devere — or De Vere — was the name she'd used a decade earlier in Toledo, when, as a clairvoyant, she also dabbled in forgery until she was arrested, found guilty, and given a nine-and-a-half-year prison sentence, of which she served less than three years. Incredibly, few people were aware ten years later that Lydia Devere and Cassie Chadwick, the supposedly rich wife of a Cleveland doctor, were one and the same.

When it was learned that Cassie Chadwick had defrauded several people and destroyed a bank in the college town of Oberlin, Ohio, some newspapers seemed less interested in that crime than the fact Mrs. Chadwick was an ex-con named Lydia Devere.

Meanwhile, people in and around Woodstock, Ontario, chuckled and said, "So THAT'S what happened to Betsy Bigley!" (Or they may have called her "Betty" or "Lylie" or "Lizzy," because she was a person of many names.)

But she was born Elizabeth Bigley in Canada in 1857, and certainly went on to lead BUT an interesting life, and while Andrew Carnegie was upset that someone had forged his name as part of a scam to live like a millionaire, he also was amused, and took no action against the woman.

“Why should I?," he said when asked if he intended to prosecute her. "Wouldn’t you be proud of the fact that your name is good for loans of $1,250,000, even when somebody else signs it? It is glory enough for me that my name is so good, even when I don’t sign it. Mrs. Chadwick has shown that my credit is A-1.”

BUT THE federal government, the state of Ohio, and creditors in Pennsylvania and Massachusetts felt punishment was due, and Mrs. Chadwick, who forged Carnegie's name on several documents, was arrested, charged with a variety of crimes against the national banking laws, and, in March, 1905, found guilty of seven of the sixteen offenses included in the indictment. She was sentenced to prison for ten years.

She had a history of faking illness, and when she returned to the Ohio Penitentiary in Columbus, under a different name this time, there were frequent reports of her condition — at one point she claimed to have gone blind — but she indeed was dying, and on October 10, 1907, her 50th birthday, she passed away in prison.

Two days earlier, the woman who hadn't professed any religion previously was baptized a Roman Catholic by the prison chaplain, putting the last weird touch on a very strange life. |

IN VIEW of what I've found over the past twelve months, I'm surprised Cassie Chadwick escaped my attention for 83 years. It's possible I heard about her while I was working at the Beacon-Journal in Akron, or earlier when I was a student at Kent State University, but if so, the name slipped out of my memory.

While I was a student, I did some banking in Kent, at one of the institutions that turned down the woman when she asked for a loan. She also struck out six miles east of Kent, at a bank in the city of Ravenna, and 15 miles to the west of Kent at a bank in Akron. Perhaps half of the bankers she visited refused her loan requests, but after Andrew Carnegie's name entered the picture, she had some spectacular success in fooling a few business men who were humiliated when their deals with the woman became public.

For me, the tale of Cassie Chadwick didn't start until I discovered fultonhistory.com, where I could read old newspapers, most of them from New York State. At the time, I was looking for obituaries and other articles about my family, which settled in Central New York after emigrating from Ireland and Poland.

Soon I became distracted by other stories from a time newspapers may have been uglier, but much more interesting than they've been for the past 40 years, each front page packed with about 15 stories, many of them irresistible.

ONE DAY I found a 1921 story about a con woman named Amelia Everts Carr, usually nicknamed "Petticoat Ponzi," became she ran a scheme similar, but on a much smaller scale than Charles Ponzi, who'd hit the news a year earlier. Then I came upon a story that compared Mrs. Carr with Cassie Chadwick, who was active long before Ponzi, operating with a similar plan — rob sucker B to pay sucker A. Of course, that meant each sucker had to cough up more money than the previous sucker.

Mrs. Chadwick, posing as clairvoyant Madame Lydia Devere, had been doing well conning people before she hit upon her Carnegie con, but after she married a respected Cleveland doctor in 1897, she upped her game, though she soon reached the point of needing a lot of money to pay off creditors who charged exorbitant interest and have enough left over to enjoy an extravagant lifestyle.

The woman's curse was being born with a desire to have pretty things, things her Canadian family couldn't provide. Result: Betsy Bigley began her life of crime as a teenager. So I'll go on and on about her life on several pages, but with this word of caution: Much of her life is a guessing game.

Elizabeth Bigley, aka Lydia Devere, aka Cassie Chadwick, aka a dozen other names, is the subject of several books, many articles available on line, a ton of newspaper articles, one Canadian TV movie, "Love and Larceny" (1985), with another ("The Duchess of Criminality") that has been under discussion since 2019.

THE SIMPLEST thing to do — after you've plowed through my piece, of course — is to check out Wikipedia, which has one of its better-written pieces, but like all stories about Cassie Chadwick, I believe it may be inaccurate in spots.

I say "may be" because no two stories about this woman agree on several points. Her biography is often a multiple choice exam in which there are no wrong answers ... because no one seems to know for sure what the right answer actually is. I'll point these things out as I go along, and admit, in the overall scheme of things, none is particularly important unless you take a Cassie Chadwick trivia quiz given by a nit-picking professor.

Perhaps the biggest bone of contention — which we'll get to much later — concerns an incident sure to be included in "The Duchess of Criminality," if it ever gets made. If true, this incident would have been key to how Cassie Chadwick convinced people she was the illegitimate daughter of Andrew Carnegie. On the other hand, there's no proof it ever happened, and I'm sure the woman was resourceful enough to find other ways to fool people, most of them men who were blinded by their own greed. While Cassie Chadwick saw them as suckers, they viewed her the same way.

In the end, they were all losers, though I suspect there was one person who profited, though he didn't live long enough to enjoy it. |

|

I refer to Elizabeth Bigley's childhood nickname as Betsy, but you'll find young Ms. Bigley called Betty, Lizzie, Lylie, and probably a few others that I missed.

Among her aliases later in life, but before she became Cassie Chadwick, were Mrs. Alice M. Bestedo, Louise Bigley, Lydia Devere, Mme. De Vere, Lydia D. Scott, Lydia Clingan (or Clingad), Mrs. C. L. Hoover, Mrs. Bagley, and my favorite, Florida G. Blythe, though I read newspaper articles that spelled the first name Florinda and Flinda. Very briefly she also was Mrs. W. S. Springsteen during her first marriage to a doctor.

Whether she was married three times or four times depends on which story you read. I lean toward the three marriage version. More later. |

Well, it was somewhere in Ontario

Likewise, her birthplace depends on your source. For example, the Wikipedia article says Elizabeth Bigley was born in Appin, a small town about 50 miles southwest of London, Ontario, but the information in the box to the right of the article lists her birthplace as Norwich, a small Ontario town about 30 miles east of London, which also shows up as her birthplace is some articles.

More often you'll see the birthplace as either Woodstock, Ontario, 40 miles northeast of London, or Eastwood, a small town just outside of Woodstock.

Whatever, Elizabeth Bigley was born in Ontario, Canada, on October 10, 1857, the year being particularly interesting when you consider her eventual claim that she was Andrew Carnegie's illigitimate daughter, especially when she reached a point when her life became a shambles in 1904 and she began telling people she was four years older than she really was. |

Five, six or eight?

Also at issue is how many children were in the family of her parents, Daniel and Mary Ann Bigley. The most frequent answer is eight — six daughters and two sons, with Elizabeth daughter number three. However, Paul Roberts, in "Queen of Sham," a story on the Woodstock Newsgroup website, calls her parents Dan and Annie, and says they had just five children — Alice, Mary, Elizabeth and Emily, and a son named Bill.

But in Cassie Chadwick's obituary, the Syracuse Herald (October 11, 1907) said the Bigley's had six children. And Charles F. Hamlyn, described as the "proprietor" of "The Woodstock Express," wrote in 1904 that Alice Bigley (who married a man named Standish York) was actually Cassie Chadwick's half-sister, indicating there might be some children in the Bigley family who were products of previous relationships by Daniel and Mary Ann. Also, perhaps in an effort to explain why Elizabeth turned out so badly, there were some who claimed the Bigley's adopted her after raising her for a while as their foster child.

Mrs. Alice York was the most-mentioned relative in stories about Mrs. Chadwick. Mrs. York had moved to San Francisco after her husband's death in 1898, and she claimed her parents were Daniel and Mary Ann Bigley, and they had eight children, all alive in 1904. But Mrs. York's recollections sometimes didn't square with a few provable facts.

Emily Bigley married a man name Daniel Pine, and they lived in Cleveland, apparently in a house purchased after Betsy Bigley became Cassie Chadwick. The Pines had two sons who show up with Aunt Cassie in photos taken in Cleveland near the Chadwick home. Another Bigley daughter (or step daughter) named Jennie married a man named Campbell, and also lived in Cleveland for awhile before returning to Canada. |

What's my line?

Again, this is nothing of earth-shaking importance, but everyone — even Alice Bigley York — seems to agree Betsy/Cassie grew up on a farm in Eastwood, Ontario, but did that make her father a farmer?

Many sources say "Yes," but others, who seem to be better informed, say Daniel Bigley was a crew boss for the Great Western Railroad, which indicates the Bigley property in Eastwood was not a working farm, though it may have had a garden that helped feed the family. |

Betsy's first crime

Those who've written about Ms. Bigley agree on how she began her life of crime, but when she did it is uncertain. Karen Abbott, in "The High Priestess of Fraudulent Finance," written in 2012 for Smithsonian Magazine, says it happened when the girl was 13. The Western Reserve Historical Society says 14, but former Cleveland Plain Dealer reporter Condon, in "Cassie Was a Lady," his chapter on the con woman in his 1967 book, "Cleveland: The Best Kept Secret (Doubleday)," says she was 18, which makes more sense.

What she did was take the envelope from a letter her parents had received from a London, Ontario, attorney, and wrote a letter to herself from that attorney, forging his signature, and making it appear the lawyer lived in London, England. In the letter, she informed herself she would soon receive an $18,000 inheritance. Author C. P. Connolly in his article, "Marvelous Cassie Chadwick" in the November, 1916, issue of McClure's magazine, says Betsy Bigley's parents couldn't read, and she convinced them she was an heiress, but even if their parents were illiterate, it's doubtful Betsy's siblings would let her get away with it.

My feeling is she didn't let her family — at least, not er parents — know about the heiress claim. For one thing, if Betsy were their daughter, common sense says the other children also were entitled to an inheritance.

However, her siblings probably knew about Betsy's prank and did not try to stop her when she took that letter to a local bank and convinced the manager to issue a check that allowed her to spend that "inheritance" in advance.

She used to check to open an account, and immediately began shopping and writing checks to cover her purchases, always making out the checks to larger amounts than what the goods cost, so that she could pocket the change. Before pulling the scam at the bank, she ordered a card that announced, "MISS BIGLEY, Heiress to $18,000." When clerks hesitated to approve a sale, Betsy showed them the card. It shouldn't have worked, but there was something about Betsy Bigley's eyes ...

Whatever it was didn't prevent her checks from bouncing, and Betsy was visited by police. She received a reprimand, but, incredibly, according to Condon, the stores did not press charges, and even let her keep her purchases. This undercut whatever lesson authorities hoped she'd learn, because what the young woman concluded was that crime could pay — and pay very well — if she kept working at it.

|

How much was that inheritance?

Not that it makes any difference now, but according to several sources, that card said, "Heiress to $15,000."

Some also say her name wasn't on the card, that it simply said "I am an heiress to $18,000," or $15,000, if you prefer.

Many years later, when, as Cassie Chadwick, she was exposed and headed for prison, a man name V. C. Lyster, identified as a wealthy stone contractor living in Ludlow, Kentucky, told the press he'd grown up in Woodstock, Ontario, and claimed to be the first boyfriend of Betsy Bigley.

Two newspapers who published stories about Lyster said his first name was Vote, which may have been an Americanized version of the German "Vogt." In any event, when he introduced himself to people, he must have sounded like a campaigning politician — "Vote Lyster."

He said, "I remember she had some cards printed, and on them she had printed: 'Miss Lizzie Bigley, heiress to $18,000'."

Like I said, hers is a multiple choice biography. |

|

|

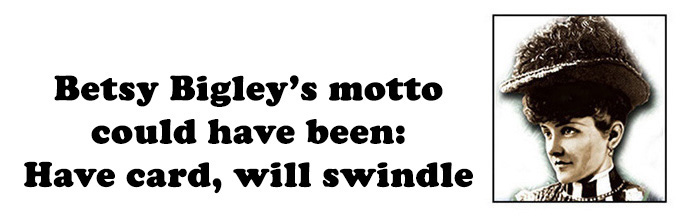

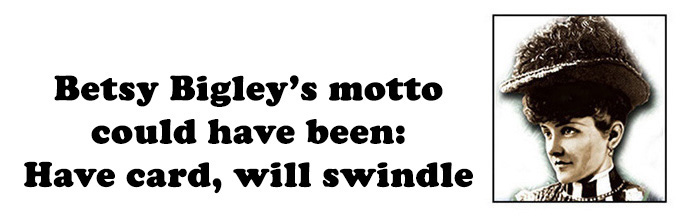

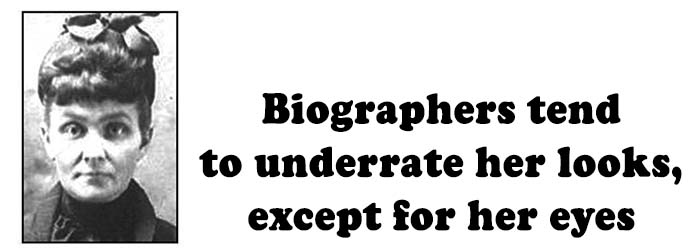

If you read a lot about Betsy Bigley/Lydia Devere/Cassie Chadwick, you quickly notice writers waste an inordinate amount of words analyzing her appeal to men. Most claim she wasn't attractive, hint that she was unattractive, even ugly or scary.

From photos I've seen, I'd say those people made their judgment on the basis of her looks in 1900, or a few years later, about the time her world came crashing down. But the photo above, taken in 1889 or 1890, when she was clairvoyant Lydia Devere in Toledo, with a prison sentence in her near future, shows an attractive woman, who would have no problem attracting men, especially since almost all of the men she conned were older, and you know what they say — "There's no fool like an old fool."

And further up the page is a photo of Betsy Bigley at the start of her crime career. If that truly is a photo of Ms. Bigley, then she was quite appealing as a young woman. |

However, there was widespread belief — supported by the photo above — that through her life what men couldn't resist were her hypnotic eyes. And, yes, people were convinced Betsy/Lydia/Cassie actually hypnotized That was especially true in the case of Lydia Devere, who separated men from their money for several years, and did it mostly without resorting to forged checks.

After her Andrew Carnegie scheme was exposed in 1904, there was still talk about about Cassie Chadwick's hypnotic eyes, which prompted Alice York to say of her sister/half-sister, “She never indicated that she was possessed of any hypnotic power. In Toledo, it is said, she hypnotized a man named Joseph Lamb, an express agent. The papers were full of it at the time, and all the talk was hypnotism. The hypnotism talk, I repeat was nonsense."

It wasn't nonsense to a deputy sheriff named Porter who accompanied Cassie Chadwick to jail in 1904. "The first time Mrs. Chadwick got a good square look at me," he told reporters, "I began to blink under the piercing gaze, until I was forced to turn my eyes in an opposite direction. I grew dizzy from the effect, but some strange power caused me to return my gaze to hers." |

At first, it may have been sex

Her sex appeal, as Lydia Devere and even in her twenties and teens as Betsy Bigley is seldom mentioned by those who write about her. In fact, most stories seem to dismiss her as having no sex appeal at all, although some people quoted in old newspaper stories go so far as to call her "a beauty" right up until the time she married Dr. Chadwick.

You'll even find an occasional claims she briefly was a prostitute and may have been operating a brothel in Cleveland when she met her final husband, Dr. Chadwick.

However, it was only in George Condon's chapter on the woman that I found the following incident, which may or may not be true, but in view of how she carried on later in life, I tend to think it contains more truth than fiction. If so, it's an interesting indication of the workings of Elizabeth Bigley's mind, even as a teenager. |

The first suggestion that Elizabeth was not an ordinary teen-ager came when, at age fifteen, she engaged in a little barnyard dalliance with a hot-eyed young farmer who lived nearby. This in itself is not extraordinary or outside the common chronicle of human weakness, but Elizabeth was said to have held off the swain until he had mortgaged his land to purchase her a diamond ring. Touched by this gesture, she then conferred her favors upon him.

|

|

| Late in life, after she and Dr. Chadwick lived separate lives — he and his daughter by his first marriage spent much time in Europe — but they were stilll married while Mrs. Chadwick supposedly gave wild parties at the large house she managed to expropriated from her husband. It is said she preferred the company of young, attractive women, and employed "French maids," as they were described, who provided the entertainment at her parties. In 1904, there was a suggesion from a former servant that Mrs. Chadwick had more than a professional relationship with the banker who was most instrumental in the success of her scam. |

What was she like?

In "The High Priestess of Fraudulent Finance," Karen Abbott says Betty Bigley

lost her hearing in one ear and developed a speech impediment, which conditioned her to speak few words and choose them with care. Her classmates found her “peculiar” and she turned inward.

George Condon in "Cassie Was a Lady," says, "Nothing really notable occurred in Elizabeth Bigley’s childhood. She was a heavy reader, it is known, and her favorite kind of literature had to do with successful women. Her parents were heard to complain at times that she was a child with entirely too much imagination.

"She always seemed absorbed in thought," said Alice York of her sister., and would sit in silence by the hour. She seemed in a trance and never would pay attention to anyone. She would come out of these thinking spells as if bewildered. At such times she would not reply when questioned. She would have melancholy spells and nothing would rouse her."

Contrary to what Condon wrote, Mrs York said, "Cassie was not a great reader."

"In speech," Mrs. York added, "she talks slowly and lisps slightly."

And when she had money, Cassie Chadwick spent it freely and was perhaps too generous to those around her, which may have hastened her downfall. |

| |

| Cassie Chadwick, Part 2 |

| |

|

|