| HOME • FAMILY • YESTERDAY • SOLVAY • STARSTRUCK • MIXED BAG |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The month was May; the year was 1892. Appropriately, perhaps, it was Friday, the 13th. At 9 a.m., Royal E. Fox, the 49-year-old paymaster of the Solvay Process Company, and his driver, James Houser, the 52-year-old foreman of the company's barn, carried two wooden boxes to a horse-drawn, two-wheeled cart. The boxes contained a week's wages for the men employed at the company's quarry in nearby Split Rock. The quarry was the source of the limestone required to produce soda ash, the essential product of a company named after a Belgian chemist who had authorized the use of his process in an American plant, which had become the largest employer in the Syracuse area. A week's wages for the 250 quarry employees amounted to $2,290.56, an almost trivial amount today, but almost five years' pay for a late 19th century laborer. The money had already been divided and placed in 250 envelopes, which meant the average envelope contained nine dollars and change. As the crow (or any other bird) flies, the quarry was about five miles from the main Solvay Process plant. However, I estimate the trip from Milton Avenue in Solvay to Split Rock was closer to eight miles, most of them uphill. Fox and Houser figured to reach their destination a few minutes after 10 o'clock. The men placed the wooden boxes under the seat of the cart. Here's an edited account of how the trip ended, according to a Syracuse newspaper that published its story just a few hours later: |

|

|

|

The robbers were long gone. It was believed the culprits had to be former quarry employees, and there was speculation over a few men who'd been fired for insubordination; a rumor spread that one of the men recently fired had once been a member of an outlaw gang out West. (Reading this more than 125 years later, I initially though this was a ridiculous idea, but I would later discover why it didn't seem far-fetched at the time.) Deputy Kratz soon made a few interesting discoveries. In a wooded area south of the company-owned road where the robbery occurred, Kratz found the masks and jackets the robbers had discarded and covered with leaves. One jacket had paint marks on it. The robbers had taken the envelopes, and left the boxes behind. Initially, it was thought a third man was waiting nearby with a wagon to drive the robbers away, but Kratz came upon Charles Mitchell, who had a farm nearby, and he seeing two gun-toting men walking through his field. He confronted the men, and one of them responded by firing two warning shots in his general direction. Kratz also talked to a teenaged boy who worked for another nearby farmer. The boy had been sent to round up a cow that had strayed off the property; while doing, the boy spotted saw two men hiding behind the stone wall. Apparently, the two men didn't see the boy. Fox, Houser, Mitchell and the boy all heard the two men speak, and agreed they sounded like native-born Americans, not recent immigrants unfamiliar with the English language. Considering how quickly the above newspaper story was put together, it was mostly accurate. Paymaster Fox, when he finally had time to concern himself with press matters, made two corrections — the robbers had three guns, not four, and he and Houser weren't thrown over the stone wall that ran along the south side of the road. Their hands were tied, then they were walked around to the other side of the wall before their legs were bound. Also, the robbers had loosened the reins and set the horse free. The cart slowly rolled off the north side of the road. Meanwhile, company treasurer Hazard did something fitting for what was widely described as a Wild West robbery — he contacted the Pinkerton Detective Agency, and hired them to investigate. On Saturday morning, Royal E. Fox and James Houser made another trip to the Split Rock quarry, this time successfully delivering $2,290.56 to men who worked a six-day week for their nine dollars in change. Again the paymaster and his driver went unarmed, thinking lightning certainly couldn't strike twice, not within 24 hours. And they were correct. Meanwhile, a Pinkerton detective was en route to Solvay, and the Onondaga County sheriff's department, plus a detective from the Syracuse police department, sorted through the statements that had been taken from the victims, farmer Mitchell, the boy, and people who reported seeing suspicious-acting men in part of Syracuse on Friday afternoon. On Saturday morning, Syracuse's Detective Becker said police had little helpful information, that officers might meet the outlaws on the streets of the city and not know them by the descriptions given out. |

|

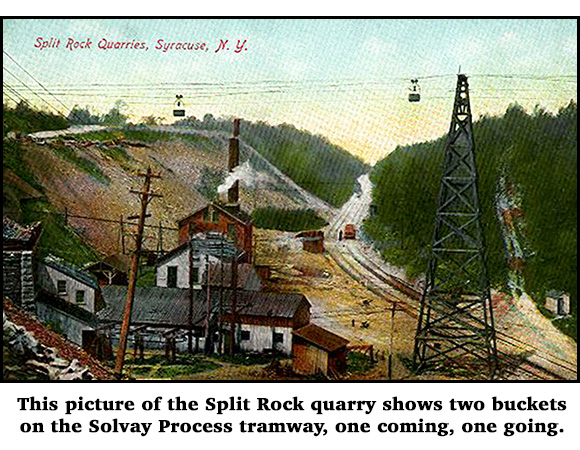

I HAVE to think Sheriff John Hoxie was pleased in July when he learned the Pinkertons had given up on the case. Well, maybe Hazard and other company officials decided it was not cost-efficient to pay the Pinkertons more money than the robbers had taken. I suspect one reason the Pinkertons were hired in the first place is that Hazard suspected the robbery was an inside job. I'm only guessing, of course, but if I'm correct, then that may be the reason the Pinkerton's had no success with the case. As thing would turn out, the only connection the robbers had with the Solvay Process Company was that one of them was married to a woman whose father worked at the main plant. Well, in those days, it was difficult to find someone in Solvay or the West Side of Syracuse who didn't work — or hadn't worked — at the Solvay Process. A few newspaper stories quoted people surprised that there was no traffic on the company-owned road during the robbery or for quite a while afterward. Those who expressed that surprise must have been unaware that the limestone from the quarry no longer was delivered to the Solvay Process by wagons. Three years earlier, over the protests of property owners affected, the Solvay Process built a tramway that carried the limestone in buckets along a three-and-a-half-mile wire highway from Split Rock to Milton Avenue in the village of Solvay. There was no reason for anyone but Royal E. Fox and his driver to be on the road to the quarry at 10 o'clock in the morning. |

|

|

|

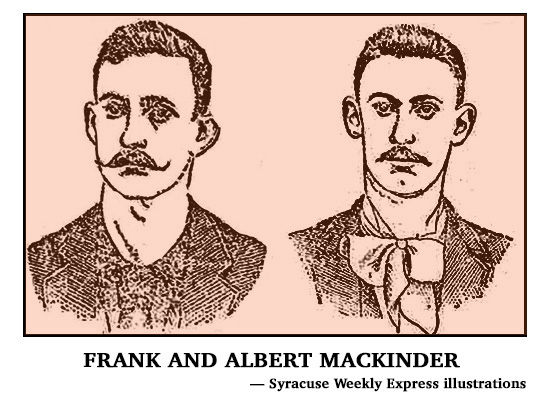

In any event, the robbery was now fully in the hands of the Onondaga County Sheriff's Department, whose boss, John Hoxie, decided one day to visit an area on the southwest side of Syracuse that was the site of a high-end housing development. Apparently, Hoxie was simply curious about what was destined to become one of the city's most desirable neighborhoods. It was called the Palmer Tract, and the man in charge of grading the area was name Charlie Hart. The two men talked for awhile before Sheriff Hoxie noticed, among Hart's equipment, a cart painted an unusual shade of carmine (that's dark red, to me). The color seemed similar to the paint blotches on one article of clothing left in the woods by the payroll robbers. Hart told the sheriff the cart had been painted recently by a man who'd worked for him until early June. Then the man quit, and left town. The man's name was Frank Mackinder. When Hoxie began asking around, he found someone who knew Frank Mackinder and his brother, Albert. This person said the Mackinders had come into some money recently, and moved away. Both brothers were married; Frank Mackinder and his wife had three children; Albert and his wife had one. Albert's father in law was a Solvay Process foreman. As luck would have it, in early August, Hodie learned the brothers and their families had returned to Syracuse, and were living in apartments in the city's ninth ward. The sheriff could have questioned the brothers' parents, or their three sisters and two brothers, but Hoxie didn't want to alert the Mackinders of his suspicions. Instead, the sheriff assigned a deputy to go door-to-door in the ninth ward, pretending to take a political census in connection with the fall election. It didn't take long to pinpoint where each brother was living. Next Hoxie lured Frank Mackinder out of the house on a ruse; the robbery suspect believed he was going to a job interview. Albert Mackinder was told police wanted to question him, but about another matter, one in which Mackinder was not involved. Both were advised not to tell their wives why they were leaving the house. Cutting to the chase, held overnight, both men confessed to the robbery, and were arrested. The next morning, their wives, concerned about their husbands' whereabout, went first to the Syracuse police department, then to the sheriff's department to report the men were missing. By this time the case was, for all practical purposes, over. The only question that remained was whether a third person was involved, and to that end, a third Mackinder, brother George, was arrested. George admitted he had sold revolvers to his brothers — a legal transaction at that time — but had no reason to believe they were planning a robbery. George was released. Frank and Albert Mackinder said they walked from the crime scene back to Charlie Hart's barn, at least three miles away. Not explained in any article is how they transported 250 pay envelopes. Mitchell, the farmer who confronted them after the robbery, didn't mention anything about either man carrying a valise or a bag. The Mackinders told police they hid the guns and the money in Hart's barn, and didn't retrieve the cash until the next week. Hart told police that both Mackinders worked for him on the day of the robbery, but finished their chores early in the morning, and had nothing to do until afternoon. Their three-hour absence wasn't even noticed. The Mackinder brothers were immediately notorious. |

|

|

|

Three months earlier, before the identities of the two outlaws were known, the same newspaper said the highway robbery rivaled the exploits of Oliver Curtis Perry, whose name meant nothing to me. He's largely forgotten today, but Perry, it turned out, was notorious at the time for being the first man to rob a train single-handed. He successfully robbed two trains, one in 1891, the other in February, 1892, operating out of Syracuse, his hometown. He had briefly left the city a few years before to be a cowboy out West, and when he was finally caught, he said he'd been part of an outlaw gang in Wyoming before returning to Syracuse. There was no evidence he was telling the truth about that. More on Perry later. THERE WAS some squabbling about the legality of the Mackinders' confessions, but the brothers were found guilty; each was sentenced to 14 years in prison, time they served in nearby Auburn. They had only been incarcerated about 15 months before Mrs. Frank Mackinder petitioned the governor of New York, Levi P. Morton (a former U. S. vice president) to pardon her husband and her brother-in-law. While the Mackinders had attracted several followers for their Wild West-like antics, they had no friends in high places. The governor denied the petition, and Mrs. Mackinder may have guessed her husband would serve the full sentence. Whatever, she later divorced him, married a man named George Hare, and had a son. I found no mention of the three children she had by Mackinder; my guess is they went to live with their grandparents or an aunt. Then a funny thing happened. Frank Mackinder was released from prison in 1903 after serving a little more than half his sentence. His ex-wife returned to him, deserting her second husband and her child. That was bad enough, but three years later, her son, Charles Hare, died, and newspapers mentioned that on his death bed, the six-year-old boy cried out for his mother, but she never came to visit him. Apparently she was never arrested or sued for anything in connection with what she had done to George Hare or their child. What happened afterward to Mr. and Mrs. Frank Mackinder and their three children, I don't know, though I did find one mention of them living in Auburn. Albert Mackinder and his wife remained in Syracuse and were still together in 1940, according to the United States Census. While the Mackinder brothers instigated one of 1892's biggest stories in the Solvay area, they were far from the most interesting people involved in the robbery. |

|

| For more on Solvay way back when, check out the Solvay-Geddes Historical Society |

| HOME | CONTACT |